Law enforcement is a high-liability profession. Lawsuits against law enforcement officers and agencies absorb an inordinate amount of personnel time and agency resources. Officers and supervisors have to be interviewed or deposed, attorney fees have to be paid, documents have to be gathered and copied, meetings are held with city officials, and insurance companies must be consulted. It all results in one expensive, time-consuming mess.

Some lawsuits against law enforcement agencies and officers are baseless, but others are not. In fact, several studies have revealed that the vast majority of citizen complaints and lawsuits filed against any law enforcement agency are generated by a small number of repeat offender personnel. One study examined citizen complaints across 165 law enforcement agencies in the state of Washington, finding that about 5% of the officers on these agencies were responsible for all of the sustained citizen complaints.1 Another study examined 15-years of citizen complaint and internal misconduct data within one urban police department in the state of New York. It found that about 6% of the officers employed by the department over those 15 years accounted for almost all of the internal and external allegations of misconduct.2

A third study examined more than 5,500 citizen complaints against officers on eight police departments from mid-sized cities. This study found that only around 5% of the officers had received more than one sustained citizen complaint, with this small group of officers accounting for more than 100 excessive force allegations, 200+ discourtesy allegations, and numerous other misconduct complaints.3 All of these studies found that while some officers receive only one sustained complaint or lawsuit during their careers, the vast majority of these problem officers accumulated 3 or more sustained citizen complaints.

These are problem-prone officers, often referred to as “bad apples,” and they create havoc within their respective government agencies. They routinely damage relations with the public, bring discredit to their agencies, and place their peers at risk for danger and lawsuits. Most of us have experienced them, and their effects, at some point within our agencies. In fact, one study involving interviews with officers from 11 police departments in Arizona revealed that most officers know who the problem officers are and resent that they often remain employed by their agencies.4 In this modern age of technology-driven transparency, the antics of these repeat problem-prone officers are also increasingly on display for the world to see—with the liability and public trust costs that come with them.

Removing Problem Officers

Removing bad apples has clear benefits for the well-being of the community, the reputation of the agency, and the morale of the department. The simplest way to deal with these problem officers is to avoid hiring them in the first place, yet many law enforcement agencies do not devote sufficient time or importance to background checks and the hiring process. Often agencies blame this lack of effort on the financial cost involved in a thorough background check, or political pressure to hire officers quickly or hire members of traditionally underrepresented groups.

After a conditional offer of employment is extended to the individual, the academy training period, field training, and probationary period continue to offer opportunities for agencies to terminate officers exhibiting problematic behaviors. Unfortunately, far too many agencies continue to try to counsel and reform these recruits or probationary officers, based on the argument that so much money has already been invested in the recruiting, hiring, and training of the individual.

Once the problematic officer successfully makes it off probation and achieves the civil service and / or union protection given to full-fledged officers, administrative and legal protections increase the difficulty of terminating such an officer. While it becomes harder to dismiss a problem officer who successfully got off probation, it is not impossible. Nevertheless, many law enforcement and government leaders worry that trying to get rid of such a problem officer is far too costly in terms of legal fees associated with the termination and the inevitable officer lawsuit.

Note that most of these concerns that prevent the effective removal of problem-prone officers tend to revolve around financial costs. Background checks are too costly. Waiting to hire the right people is too costly. Terminating a recruit or probationary officer in which thousands of dollars have already been invested is too costly. Terminating a problem-prone full officer, and defending against the resulting lawsuit, is too costly. However, has anyone ever sat down and done the math to examine these costs and compare it to the cost of the alternative? What is the financial cost of having a problem-prone officer on your department?

Estimating the Civil Liability Costs of the Problem Officer

To estimate the average annual civil liability cost of a single problem-prone officer in a law enforcement agency, data from several sources were used. A search of a number of online newspapers was conducted to locate articles that reported annual payouts to citizens by cities for lawsuits over police misconduct allegations. Articles published since 2010 reported multiple years’ worth of data about civil court payouts, specifically for police misconduct in 25 agencies from 15 states. Only jurisdictions for which multiple years’ worth of data were used as any given municipality could have a single abnormally large settlement in a single year. It is important to note that these payouts were only for lawsuits from citizens, and not internal officer lawsuits. These payout costs also only accounted for money paid to the plaintiff, and do not include other costs incurred by the jurisdiction such as litigation expenses and insurance fees.

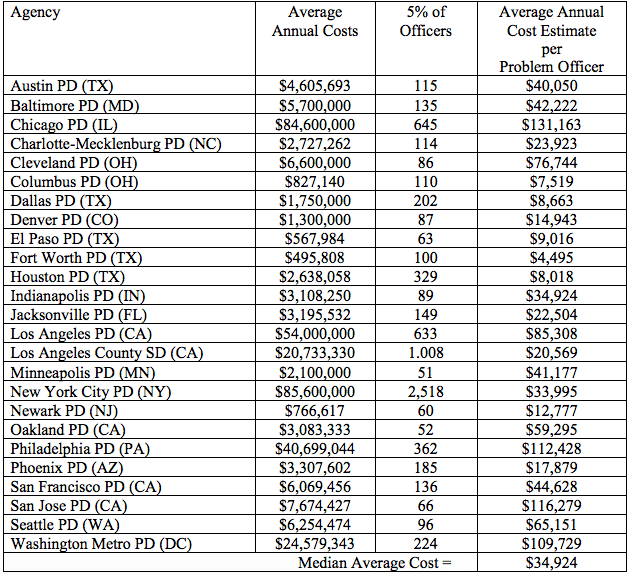

Federal government data from the 2015 Census of State and Local Governments was accessed to determine the total number of full and part-time officers of each of these law enforcement agencies. Based on the prior research suggesting that about 5% of officers account for the vast majority of misconduct complaints and lawsuits, this percentage was used to estimate the number of problem officers with which each department might be struggling. The average annual payout by the agency was then divided by the estimated number of problem-prone officers to estimate the average annual payout for each jurisdiction-per-problem-officer. The results are displayed in the table below.

The average annual cost estimate per problem officer ranged from a low of $4,495 for Fort Worth, to a high of $131,163 for Chicago. Since jurisdictions can vary dramatically in their payouts due to differing attitudes of each local court, and differences in the egregiousness of officer misconduct, it is best to consider the average cost of the whole sample using the median cost. The average median cost in this sample was $34,924 per problem officer per year. If such an officer serves a 25-year career, the law enforcement agency can expect to pay about $873,100 in compensation to citizens suing the department. Again, it is important to note that these figures do not even include costs for legal defense, insurance rates, or internal lawsuits over officer grievances filed because of this officer, so it is reasonable to expect to pay about twice as much for this officer’s misbehavior when all expenses are considered.

Is It Worth It?

Some law enforcement and government leaders cite financial costs as a barrier to properly investigating applicants, terminating poorly performing trainees, and dismissing serious misconduct officers. In these cases, it is important to weigh these decisions against the estimate developed here. If your jurisdiction does not expend a few extra thousand dollars on thorough background checks of job applicants, then you very well could end up paying an addition $35,000+ every year in civil case payouts if you end up hiring a problem-prone officer. Likewise, jurisdictions will save money if they terminate a problem-prone officer for cause and end up paying less than $35,000 a year in legal costs to win any arbitration or wrongful termination hearings. The reality is that the legal fees associated with defending accusations of wrongful termination from one former officer are generally much less than $35,000 per year if you win.

Even if you lose, one study in Florida found that the average payout for a wrongful termination lawsuit in that state was only $40,000.5 Which would you rather do? Would you rather pay $40,000 plus a few thousand dollars in litigation fees to rid your agency of a serious problem-prone officer, or continue to pay $35,000 in payouts to citizens plus legal and insurance fees each year for many years into the future? Biting the cost bullet now to prevent continued future loses later is often the right decision. Agency funds well spent now to ensure problem-prone officers are removed or not hired can reap significant financial savings for the agency later.

References

1 Dugan, J. R., & Breda, D. R. (1991). Complaints about police officers: A comparison among types and agencies. Journal of Criminal Justice, 19, 165–171.

2 Harris, C. J. (2010). Pathways of Misconduct. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

3 Terrill, W., & Ingram, J. R. (2016). Citizen complaints against the police: an eight city examination. Police Quarterly, 19, 150-179.

4 Haarr, R. N. (1997). They’re making a bad name for the department: Exploring the link between organizational commitment and police occupational deviance in a police patrol bureau. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 20(4), 786-812.

5 Cutting Edge Recruiting Solutions (2012). Officer Lawsuits. Boca Raton, FL: CERS.