“Why?” This is a one-word question that requests clarification, reasoning, or purpose of some thing or some request. Asking ‘why’ is a universally human concept. Aristotle pointed this out over 2,300 years ago when he said, “All human beings, by nature, desire to know.”1 It is also a truly American word. In the United States, the greatest country in the history of the planet, we have taken the question why to the next level.

During the American Revolution, General George Washington realized he needed help creating a professional army out of his rabble of untrained, undisciplined farmers and tradesmen. Benjamin Franklin contacted and recruited Baron Friedrich von Steuben from Europe to help. Baron von Steuben, who had joined the Prussian army at the age of 17, was a combat veteran with 30 years of military service in numerous wars across Europe. He had trained and led soldiers in many military campaigns against Russia, Poland, and France.2 If anyone knew how to train and lead soldiers, it was him. But then he met the Americans.

Baron von Steuben arrived at Valley Forge to begin training these new American recruits and quickly learned that the training techniques he used in Europe were ineffective here. When he gave orders, he immediately received pushback from the American soldiers who questioned everything he did. He was used to European soldiers who rarely questioned orders.3 Frustrated, von Steuben wrote in his personal diary the following entry.

In Europe, you say to your soldier, “Do this” and he does it. But I am obliged to say to the American, “This is why you ought to do this,” and only then does he do it.4

If he had been paying attention to recent world events, Baron von Steuben would not have been so surprised. These were the same people who asked, “Why do we have to pay a tax on tea we didn’t ask for?” and then dumped the tea into Boston Harbor. These were the same people who asked, “Why are we considered British citizens, pay taxes to Britain, but lack the right to elect leaders to 2 Parliament?” These were the same people who asked, “Why do we have to obey a king we have never met, who lives in a land we have never seen?” It was all of these “why” questions that brought about the creation of the United States of America. The practice of questioning authority is in our national DNA.

Want More Proof?

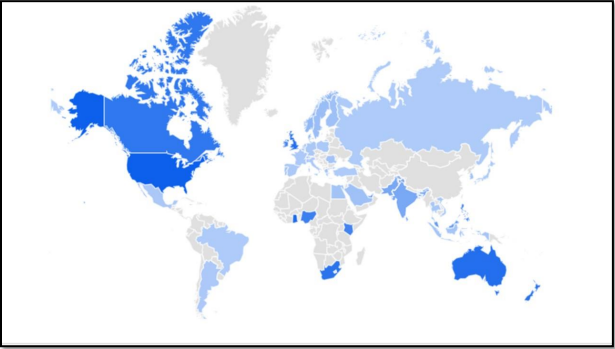

Are you still unconvinced? Look at the graphic below. This is a map of Google Analytics data showing the prevalence of people Googling the word ‘why.’ The shade of each country indicates how often people in that country have Googled the word ‘why.’ The darker the shade indicates the more people who have Googled the word ‘why’ in some context. Nobody tops the United States when it comes to asking, “Why?”

Source: Google Analytics

Think of your kids. How often do they ask why when you tell them to do something? Sometimes you might reply with, “Because I said so.” You might even say, “Because I’m your parent.” How well did that work for you? Did that type of response diffuse the situation and did your teenager respond with, “Oh, how stupid of me. I must have forgotten you were my parent.” Of course it didn’t work like that. Responses that don’t try to explain why do not work.

Think about your work life. Have you ever come to a roll call shift briefing and been given a brief memo or email from the command staff creating a major change in operational policy with no explanation for the change? Isn’t that frustrating? Didn’t it make you ask your sergeant or lieutenant, “Why the change? What is this all about?” Of course it did, because you’re an American. 3

It should be no surprise, therefore, that people you encounter on the street do the same. American people will often respond to requests you make as a law enforcement officer with the very American response of, “Why?” This is usually because they truly want to know the reasoning behind your request to see if your authority appears legitimate. It is also because it is in their DNA as Americans. Remember, we are the descendants of the people who went to war when they felt the authorities over them were acting without legitimacy. So why don’t we just quickly tell them?

How to Explain Why

In our Surviving Verbal Conflict© courses, we train public safety professionals to start off citizen interactions with a quick explanation of why the encounter is taking place. We train officers that, if safety permits, they should begin encounters with a ‘Meet & Greet’ – a quick introduction and explanation for the encounter. Here is an example. “Good evening sir, I’m Officer Dolan with the police department. The reason I’m here is that we received some calls about screaming coming from this apartment. Can I talk to you about that?” If you opened your door to a knock at 10:00 p.m. and found a police officer (or two) standing there, wouldn’t you want to know why they were there? Even if you had previously been arguing with your partner, and suspected that was the reason for the police presence, you would probably still want to confirm that this was why they had come. So why not just take care of the inevitable question right off of the bat?

What if you were driving along in your personal vehicle and a patrol car pulled you over? My guess is that your first thoughts would be, “Why am I getting pulled over?” I would argue that the typical citizen is no different. Even if the driver suspects the reason for the stop, you know full well that he or she is going to ask anyhow. It’s the American thing to do, so of course they will likely be unhappy if you begin the encounter with a “license and registration” demand. Worse yet is the guessing game. If an officer stopped me and asked, “Do you know why I stopped you?” my first New Yorker gut instinct would be to want to reply in a sarcastic tone, “Oh, so you think I’m clairvoyant? No, (expletive), I don’t know why you stopped me. Why don’t you just tell me?”

Some people with cynical views of the police may think they already know why they are being stopped, such as believing it is because of their race. Asking the “Know why I stopped you?” question opens up an opportunity for these individuals to accuse you of racial profiling with their response. This is often negated if you simply explain from the start the legitimate reason for the stop. “Good afternoon sir, I’m Officer Dolan with the city police department. I stopped you because your rear license plate is missing.”

Conclusion

Keeping in mind that asking “Why?” is an American thing to do, we should take all reasonable steps to give a quick answer to demonstrate the legitimacy behind our requests and actions. Preemptively explain why when making requests, such as “Sir, for your safety and mine, would you please stay in the car” or “Folks, could everyone please back up so we can get the ambulance in here when it arrives?” When people do ask, don’t take it as an insult or a 4 challenge to your authority. Simply respond with a quick explanation that supports your legitimacy and lets you continue doing your job.

References

1 Aristotle (320 B.C.). Metaphysics. Athens, Greece.

2 Lockhart, P. (2008). The Drillmaster of Valley Forge: The Baron de Steuben and the Making of the American Army. Washington, DC: Smithsonian.

3 Ibid.

4 Ibid.