The recruiting and retention of qualified law enforcement officers continues to be a struggle for most law enforcement agencies. In many agencies, it has reached a crisis level. Many blame the current hiring and retention struggles primarily on the decline in public support for the police, fueled by biased media coverage and exploited by politicians and activist groups. Obviously, these conditions have not helped police recruiting and retention, but other root causes of the problems run much deeper and are, in many ways, more troubling in the long-term.

These root cause challenges are shared by those struggling to hire qualified applicants to replace retiring teachers, firefighters, nurses and countless other professionals. And these challenges will likely have effects lasting for decades. As a result, rather than simply trying to weather a short-term storm, the likes of which law enforcement has seen with some frequency during times of low unemployment, we must consider how to survive the chilling effects of a recruiting and retention ice age that appears likely to last for many years to come.

The Major Causes

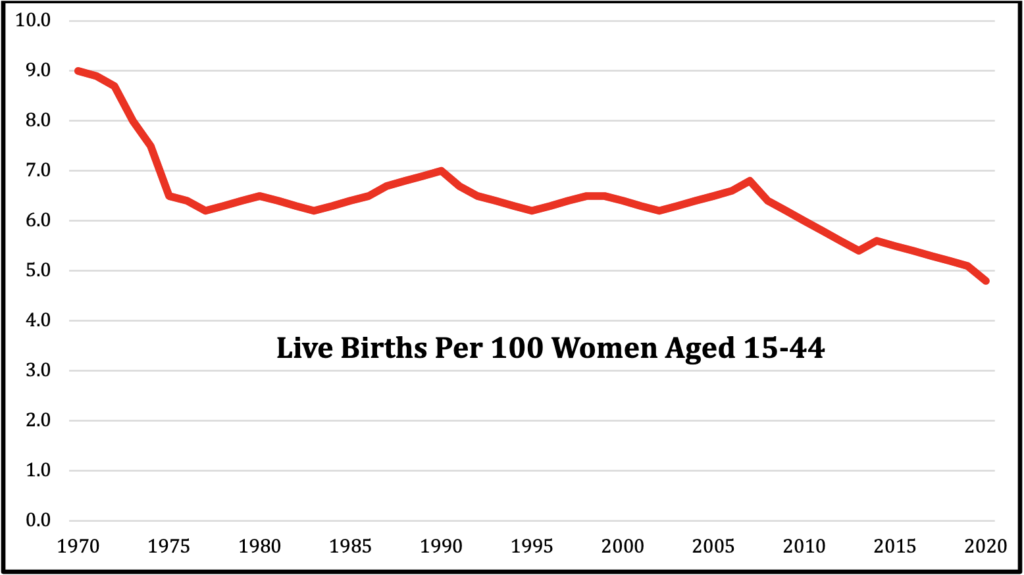

First, there are simply fewer Americans available to enter the workforce today. As demonstrated in Figure 1 below, despite some year-to-year fluctuations, the birth rate in the U.S. has been declining since 1970. In the “good old days” of gymnasiums packed with police applicants, there were simply many more young people looking for work.

Furthermore, the steep decline in birth rates that began with the Great Recession of 2008 has not yet bottomed out. In the coming years, there will only be fewer and fewer Americans available to enter the workforce. There will not be more Americans available to the workforce until the 2040s at the earliest, and only then if the birth rate trend reverses within the next few years.i

Figure 1. United States Birth Rate 1970-2020

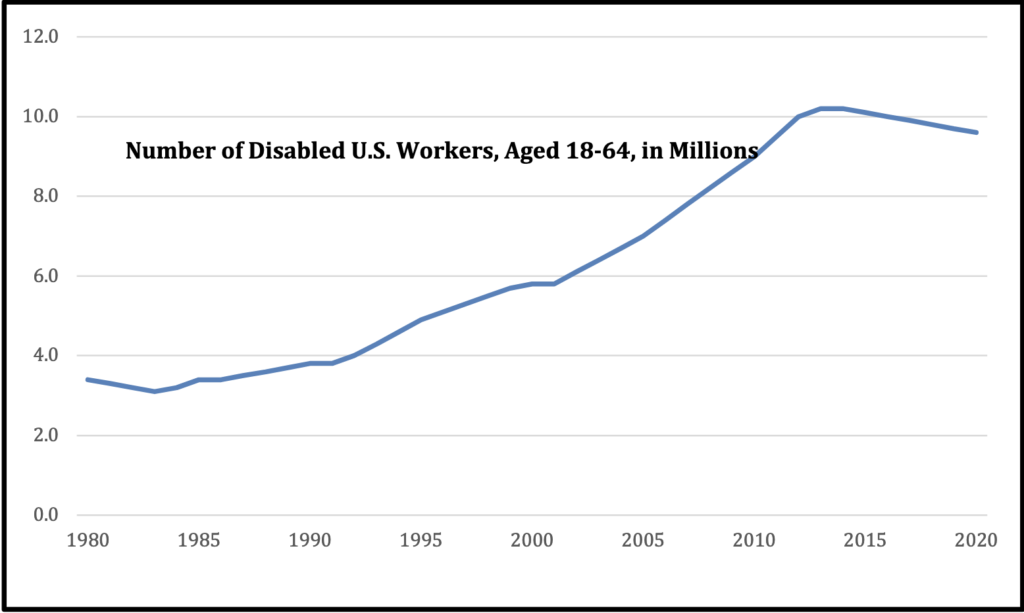

Secondly, of the individuals between the ages of 21 and 40 in America today, many cannot meet the bona fide minimum requirements for employment in law enforcement. In 1970, only 1.8 million American workers ages 18-64 received Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) income. Fifty years later, in 2020, that number had grown by 426% to approximately 9.5 million, while the U.S. population only increased by 63%.ii Figure 2 below shows the number of Americans each year between ages 18 and 65 who received Social Security Disability Income (SSDI) from 1980 through 2020. As this figure reveals, the rise in recent decades has been tremendous. This rise in disability claims indicates that, in addition to the fact there are fewer workforce-aged Americans each year, fewer and fewer of these Americans are able to work, especially in a demanding career field such as law enforcement.

Figure 2. Number of Worker Beneficiaries of Social Security Disability Income, 1980-2020

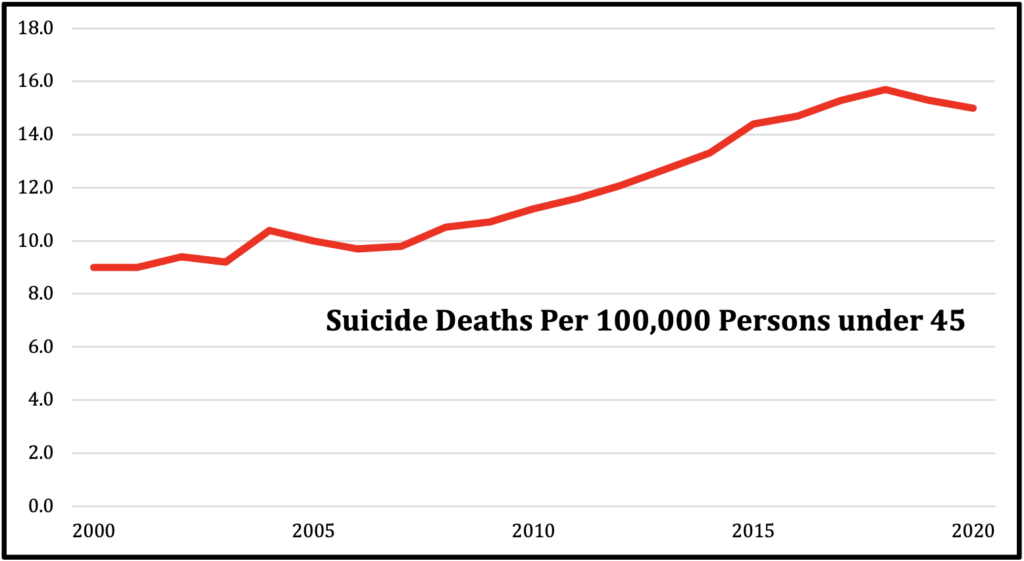

Mental health disorders, substance abuse issues, and suicide have skyrocketed since 2008, making it more difficult to find psychologically qualified candidates. According to research by the Mental Health America Association, approximately 20% of American adults today suffer from a diagnosable mental illness.iii When combined with the troubling rise in “deaths of despair”—drug overdose, suicide, alcohol-induced liver failure, etc.—among younger Americans, it becomes clear that the rise in drug addiction and mental health disorders is a significant factor in the shrinking pool of young Americans qualified for police work.iv

Figure 3 below depicts the suicide rate in the U.S. for persons under the age of 45 since 2000. As this figure reveals, the suicide rate has been on a steady incline since 2008. The suicide rate for this age range in 2020 was 67% more than the rate in 2000. This troubling data regarding suicide is clearly an indicator of a broader mental health crisis among young Americans—the very same pool of applicants that law enforcement traditionally relies upon to replenish the ranks year after year.

Figure 3. United States Suicide Rate for Persons under Age 45, 2000-2020

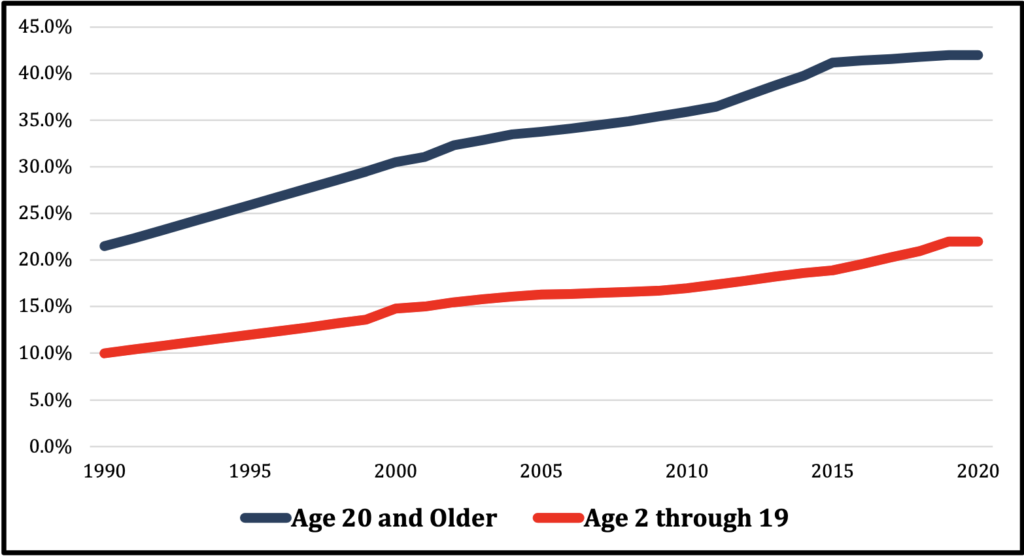

Obesity in America continues to increase as overall physical fitness declines, making it difficult to find physically qualified candidates. According to the Centers of Disease Control, in 2020 the percentage of Americans over age 20 who were obese (meaning greater than 30% body fat) exceeded 42%, as well as 22% of youths aged 12-19.v Figure 4 below reveals the obesity trend in the U.S. among adults and children since 1990.

The military’s recent struggles in recruiting are attributable in part to this rise in obesity, and there seems to be no reason to think that the law enforcement profession will not be similarly impacted in its recruiting efforts.vi

Figure 4. Percentage of Obese Persons in the United States, 1990-2020

If all that were not enough, the recent social and economic changes since 2020 have resulted in a “Great Resignation,” an unprecedented labor market trend in which employees have resigned from their jobs in massive numbers to pursue jobs with higher pay, better working conditions or better work-life balance—the things law enforcement careers may not be able to offer.vii

For all these reasons, every civil service profession is desperately searching for quality workers. Fire departments and emergency medical services agencies have been experiencing personnel shortages for several years now.viii School districts across the nation have been struggling to hire enough teachers and counselors.ix The military is now at an all-time low in its ability to recruit new soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines—even among the officer ranks.x The widespread nature of these recruiting challenges indicates that, even without the unfairly negative treatment of police in the public discourse, the shrinking pool of qualified applicants is a structural problem that goes beyond political scapegoating or the ups and downs of public support.

Through our efforts to assist law enforcement agencies with their recruiting and retention efforts, we have repeatedly observed that there are some agencies that are meeting their staffing goals—often by attracting lateral hires seeking community support, better pay and improved working conditions. But even these successful agencies rarely report sufficient increases in qualified applicants entering the profession as opposed to leaving another law enforcement agency as a lateral hire. And most agencies, especially large and mid-size urban agencies, are continually struggling to find qualified candidates.

So, what can be done? It is clear that, due to changing population demographics and characteristics, the shortage of qualified applicants will likely be with us for many years to come. It is not enough to hunker down and simply try to weather the storm and wait out the personnel shortage without making difficult but crucial changes to agency operations. This does not appear to be a short-term staffing problem—it looks more like a long-term personnel shortage that will require law enforcement agencies to adapt.

Response Options

It is time to face the fact that personnel shortages show every sign of remaining for the foreseeable future. It is time to explore ways in which law enforcement agencies can continue to function with personnel numbers far lower than in the past. Below we will present several ideas that we at the Dolan Consulting Group offer for your consideration. Please bear in mind that we realize not all of these ideas are feasible for your particular agency. You know your community, its leadership and governance and what your citizens will tolerate. Some of these ideas may work in one community, but not in another. You are the best judge of what will work where you serve. Nevertheless, steps must be taken to effectively operate long-term in this new environment of severe personnel shortages for the long term.

Redeployment of Existing Personnel

What is the most basic function of the law enforcement agency? It is to respond to citizen calls for service, especially emergency calls for help. If your agency fails in this mission, it will inevitably lose public support for the police in your community. Therefore, we must prioritize the patrol function of our organizations.

We need to acknowledge that some agencies can no longer afford to keep many of their specialized units and administrative positions—not because these positions are not valuable, but because the staffing crisis calls for a triage approach that involves difficult decisions regarding prioritization. Some agencies may also have to scrutinize a variety of administrative day-shift positions to ensure that they are absolutely necessary to agency operations.

Is your agency able to keep enough uniformed personnel on the street, 24-hours a day, 7-days a week, and keep your constituents satisfied with response times, without burning out your youngest officers through hours and hours of mandatory overtime? If not, then you need to take a hard look at the other elements of your organization. It may be time for some law enforcement agencies to return to a generalist model, where the officer on the beat is responsible for follow-up investigations and engaging in community relations efforts between handling calls for service, rather than specializing in an era of severe understaffing.

Supplementing with Technology

Are there ways that we can use technology to help fill in the personnel gaps? Using Geographic Information Systems (GIS) for crime mapping can help us predict where and when calls for service are most likely to be concentrated, allowing command staff to schedule and position patrol units where and when they will be needed most. Surveillance CCTV cameras that continually record, combined with license plate readers, concentrated in areas with the highest crime and call for service volume can help solve cases faster. These devices may capture video images of street crimes reported to the police, and identify the suspect vehicles involved. They may also prove a deterrent once the criminal element realizes their effectiveness. Aerial drones also appear to have a future in aiding in rapid response to emergency calls by gathering video evidence and following potential suspects until officers arrive on the scene.

Limiting Your Agency’s Roles

The police cannot do all things for all people. And if an agency does not have the capacity to effectively respond to some quality-of-life calls for service, that reality should be honestly communicated to the public rather than quietly becoming the reality until news media or community groups recognize that the service is not being provided.

We need to prioritize which functions the police will perform in your community and identify which functions your agency no longer has the budget or personnel to perform. Responding to crimes and emergencies is a priority. But what other duties does your agency currently perform that you may have to de-emphasize? How about crossing guards or other non-emergency traffic control functions that could be performed by another entity or civilian company? Why are crash reports or parking enforcement activities necessarily a law enforcement agency function? It may be time for your agency to sit down with local government leaders to identify which service functions are most important for the community and then focus solely on those functions. The police cannot do it all, especially in the face of the personal shortages that are likely to persist.

Civilianization or Privatization?

Some agencies may have to look into the options available for civilianization or privatization to fill the gaps that we’ve discussed. Civilianization involves examining the personnel roles within your organization and determining if there are any roles currently occupied by a sworn officer that could be performed by a non-sworn individual instead. Does a recruiter, training supervisor or instructor, background investigator or any position in office administration have to be filled by a sworn officer? If any of these roles are performed better by someone with police experience, could a retired officer fill this role?

Privatization, on the other hand, is the act of outsourcing to a non-governmental agency some functions that your agency no longer has the time or personnel to perform. Some common forms of privatization in use today within law enforcement include outsourcing traffic control, parking and traffic enforcement, counseling, training and recruiting functions. Again, every community is different and you know better than anyone what would be accepted in your particular community. But it might be worth the time to take a hard look at the personnel positions within your agency and see if there are any roles or functions that could be performed sufficiently by non-sworn personnel or an outside company.

Radical Personnel Policy Changes

It may be beneficial to re-examine your agency’s personnel policies to see if any legitimate changes could be made to improve retention and “widen the net” to attract more potential employees, without damaging the integrity of the profession. We at the Dolan Consulting Group are strongly opposed to lowering hiring standards regarding honesty, morality and personal integrity, such as a past record of lying, severe mental illness or engaging in serious criminal behavior. But can we legitimately and realistically consider lowering other existing standards?

What about your approach to physical fitness? The rise in obesity among young Americans presents a serious challenge to law enforcement recruiting. Agencies across the country report that otherwise qualified applicants are regularly disqualified due to poor physical fitness. It would seem that improving the physical fitness of a candidate who has the character, temperament and integrity necessary to serve as an officer is in many ways a more promising undertaking than hiring a candidate who is physically fit but lacking in character or mental fitness.

Instead of simply lowering fitness standards, should agency leaders consider taking a more active role in helping applicants get into physical shape? As a comparator, none of the military branches expect their new recruits to be able to pass their respective physical fitness tests on the day the recruit enlists. The military long ago realized that it recruits from a cross-section of the American population that includes people who are physically out of shape. The military takes on the responsibility for getting new recruits into physical shape during basic training.

Should internship and cadet programs for those too young to serve as sworn officers include significant physical fitness training components? Are there other strategies that agencies can deploy to help candidates become more physically fit over time before entering the formal hiring process? The prevalence of obesity suggests that doing things the way we’ve always done them in this area of recruiting is doomed to produce the same results that have been seen in recent years.

Furthermore, if your agency decides to retain its entry-level weight and physical fitness requirements, why is it necessary to place a maximum age cap on your applicants? If fitness is important, what does it matter how old an individual is if she or he is not overweight and can pass your agency’s physical agility test?

Citizenship is another issue to consider. If an individual meets all of your agency’s standards for education, physical fitness, moral integrity, intelligence and a good work history, is it truly necessary that she or he is a U.S. citizen? Bear in mind that throughout its entire existence, from the Revolutionary War through today, there has never been a period when the U.S. military did not have foreign nationals serving within its ranks. For many of these immigrant soldiers, it has been their path to citizenship.xi Also consider the fact that prior to the mid-twentieth century, a substantial portion of the police officers working in our nation’s large cities were new immigrants, especially those from Ireland, Italy and Eastern Europe.xii This might be another option for widening the net for your applicant pool.

Your agency may want to consider adopting radical leave policies. The current personnel shortage has already caused many agencies to relax their restrictions on lateral entries of officers from other agencies. Why would these same agencies require their own good officers to go back through the entire selection and training process again after a voluntary separation for a few years? When you have an officer who has served your agency well for several years, why would you want to deter that officer from returning to your organization after voluntarily leaving for a few years to raise a family, try their hand in business, go back to school or to work in a less stressful office environment? There may well be better ways to handle these situations rather than requiring the officer to resign permanently.

Your agency may want to brainstorm ways to permit officers to do these things—start a side business, raise a family, go to school, etc.—through part-time employment or extended leave options. It is understandably frustrating to law enforcement leaders to discuss part-time officer positions and extended leaves of absence when there is a serious need for more full-time officers right now. But, in the long-term, continuing to plow ahead in the way that we’ve always done things may only serve to make staffing issues much worse. And these flexible leave and part-time policies could also be a benefit that attracts more potential new recruits.

Partnerships with Other Organizations

Finally, partnerships with other agencies may also be an option to consider. Firefighters and EMTs already respond to a high volume of mental health calls, safely treat the immediate conditions, and connect the individuals to longer-term mental health services, often by transporting to a hospital. Fire and EMS departments may be better suited than law enforcement agencies for participating in crisis intervention teams (CIT), with a police component only present to provide protection for the immediate call. There may be other similar roles that law enforcement agencies presently perform that should be shared with, or passed on to, other existing government entities.

Conclusion

The American workforce has changed, and it is a long-term change. There are fewer young Americans available for the workforce than in past decades, and there will be even fewer in the years to come. Of the few individuals we have to choose from in the labor pool, the proportion that meet law enforcement’s physical, moral and mental standards is declining every year.

This is not a simple storm we can wait out. It is a long-term freeze on our labor force—it is likely more akin to an ice age. In order to continue to perform your public safety functions in society, the law enforcement profession will need to make some radical changes. Agency leaders and the communities they serve need to take a hard look at how we have done things—often great things—in the past, but realize we no longer have the qualified personnel to continue doing them in the future.

We must avoid making dangerous compromises, such as lowering our standards regarding applicant mental health or moral integrity. The authority to arrest and use physical force endowed upon law enforcement officers prevents us from compromising the integrity of the profession in that manner. But are there other standards that have been applied in the past that cannot withstand close scrutiny today? Are there staffing and deployment priorities that need to be examined more closely in the face of the new personnel realities?

Now is the time to plan for the lean years ahead and find ways to weather this long-term personnel shortage. If agency leaders do not make changes, the changes will be made for them—likely by elected officials who lack the expertise necessary to make fundamental changes without unnecessarily compromising community safety. Law enforcement leaders should consider adapting and adapting quickly.

About the Authors

Matt Dolan, J.D.

Matt Dolan is a licensed attorney who specializes in training and advising public safety agencies in matters of legal liability, risk management and ethical leadership. His training focuses on helping agency leaders create ethically and legally sound policies and procedures as a proactive means of minimizing liability and maximizing agency effectiveness.

A member of a law enforcement family dating back three generations, he serves as both Director and Public Safety Instructor with Dolan Consulting Group.

His training courses include Internal Affairs Investigations: Legal Liability and Best Practices, Supervisor Liability for Law Enforcement, Recruiting and Hiring for Law Enforcement, Confronting the Toxic Officer, Performance Evaluations for Public Safety, Making Discipline Stick®, and Confronting Bias in Law Enforcement.

Richard R. Johnson, Ph.D.

Richard R. Johnson, PhD, is a trainer and researcher with Dolan Consulting Group. He has decades of experience teaching and training on various topics associated with criminal justice, and has conducted research on a variety of topics related to crime and law enforcement. He holds a bachelor’s degree in public administration and criminal justice from the School of Public and Environmental Affairs (SPEA) at Indiana University, with a minor in social psychology. He possesses a master’s degree in criminology from Indiana State University. He earned his doctorate in criminal justice from the School of Criminal Justice at the University of Cincinnati with concentrations in policing and criminal justice administration.

Dr. Johnson has published more than 50 articles on various criminal justice topics in academic research journals, including Justice Quarterly, Crime & Delinquency, Criminal Justice & Behavior, Journal of Criminal Justice, and Police Quarterly. He has also published more than a dozen articles in law enforcement trade journals such as the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, Police Chief, Law & Order, National Sheriff, and Ohio Police Chief. His research has primarily focused on police-citizen interactions, justice system responses to domestic violence, and issues of police administration and management. Dr. Johnson retired as a full professor of criminal justice at the University of Toledo in 2016.

Prior to his academic career, Dr. Johnson served several years working within the criminal justice system. He served as a trooper with the Indiana State Police, working uniformed patrol in Northwest Indiana. He served as a criminal investigator with the Kane County State’s Attorney Office in Illinois, where he investigated domestic violence and child sexual assault cases. He served as an intensive probation officer for felony domestic violence offenders with the Illinois 16th Judicial Circuit. Dr. Johnson is also a proud military veteran having served as a military police officer with the U.S. Air Force and Air National Guard, including active duty service after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Before that, he served as an infantry soldier and field medic in the U.S. Army and Army National Guard.