De-policing (the practice of field personnel pulling back from proactive policing activities) has been on the rise across the nation since the fall of 2014, primarily in response to negative media attention and political protests targeting the police. In the wake of anti-police sentiments and protests, some law enforcement officers and agencies made the intentional decision to either stop or significantly reduce their proactive policing activities, such as proactive stops, searches and arrests.[i]

Then, during the pandemic of 2020-2021, many law enforcement agencies prudently pulled back temporarily from enforcing minor violations of the law. This was done to reduce the spread of the virus within jail populations and ease the caseloads for the traffic and criminal courts that had drastically cut back on their in-person operations.[ii]

However, now that the courts and jails are back to full operational status, and we are seeing nationwide spikes in traffic crashes and violent crime, it is time to consider resuming proactive policing strategies. Social science research evidence reveals a correlation between proactive policing activities, such as proactive stops and the targeting of crime and traffic hot spots for proactive patrols, and a reduction in social problems such as crime and serious traffic crashes.[iii] After several years of pulling back, it may be time to overcome officer resistance and inertia and get back to proactive police work.

Crime and Traffic Problems on the Rise

It is an irrefutable fact that crime, especially violent crime, is on the rise in the United States. This reality is reflected in Americans’ increasing fear of crime. In 2020, the Gallup Poll revealed that 78% of the Americans surveyed believed there was more crime in the nation during 2020 than in 2019. In 2021, the Gallup Poll revealed 70% of Americans believed there was even more crime in the nation during 2021 than in 2020. Again, in 2022, the Gallup Poll revealed that 78% of Americans believed there was yet again more crime in the nation during 2022 than in 2021. When asked about conditions at their local level, 38% of those surveyed said crime had increased in their neighborhood in 2020, 45% said it had increased in 2021, and 56% said it had increased in 2022.[iv] Similarly, a POLITICO poll in the fall of 2022 found 67% of those surveyed thought violent crime was increasing nationally.[v]

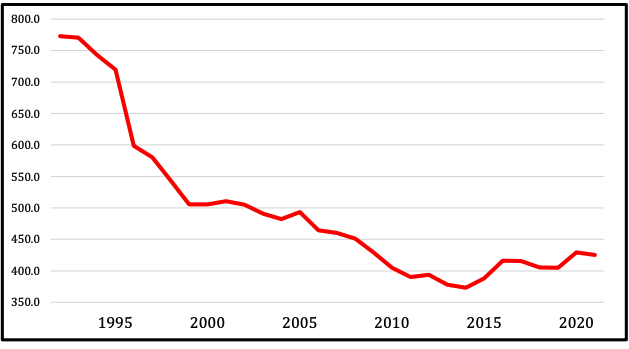

Looking at historic trends, FBI Uniform Crime Report data reveals a decline in violent crime in the U.S. since its peak in 1993 until 2015. In response to the high rates of violent crime in the late 1980s and early 1990s, law enforcement agencies began focusing on evidence-based, proactive policing strategies, while the courts began increasing incarceration rates, especially for violent offenders. Not surprisingly, the nation’s violent crime rate (including the homicide rate) fell continuously after 1993, when those proactive strategies began to be utilized. That trend of decline bottomed out in 2015, coinciding with the surge in nationwide anti-police protests, political activism, negative media campaigns and the resulting rise of de-policing.

Using FBI Uniform Crime Report data, Table 1 below reveals the violent crime rate trend in the U.S. from 1992 through 2021. There is no disputing the decline in the violent crime rate when proactive policing strategies were widely in use across the nation (1992-2014), and the uptick in violent crime beginning in 2015, when the de-policing phenomenon began to grow.

Table 1. U.S. Violent Crime Rate (per 100,000 persons) 1992-2021

Data Source: FBI Uniform Crime Reports

Table 2 below reveals a similar trend, specifically for the U.S. homicide rate, over the same period of time. When proactive policing strategies were commonly employed across the nation, the U.S. homicide rate was in decline. When the de-policing phenomenon began, the homicide rate began to rise again. While the official statistics for 2022 will not be available for another year or so, media reports from the nation’s major cities suggested that the year 2022 was just as violent as 2021.[vi] The current trend, and when it began, reveals a clear conclusion—de-policing leads to increased violent crime and homicides.

Table 2. U.S. Homicide Rate (per 100,000 persons) 1992-2021

Data Source: FBI Uniform Crime Reports

Official statistics on fatal motor vehicle crashes within the U.S. also show an interesting and troubling trend. Table 3 below shows the total number of drivers involved in fatal motor vehicle crashes in the U.S. from 1992 through 2020, the most recent year when data was available from the U.S. Department of Transportation. As Table 3 reveals, prior to 2015, the number of fatal crashes had generally been in either stagnation or decline up until 2015. Interestingly, the number of fatal crashes began to surge upward in 2015 and continues to rise. Even during the lockdowns of 2020, when there were far fewer people on the roadways (and many law enforcement agencies were refraining from making proactive vehicle stops), the number of fatal crashes was much higher than in past years.

Are these trends a coincidence or the result of de-policing? We believe these trends provide clear evidence that proactive policing matters. People are dying, and it is time for it to stop. It is time for political leaders and law enforcement officials to reverse these trends.

Local political leaders need to encourage and expect their law enforcement officers to return to the proactive policing strategies that have proven to reduce crime during the last crime surge of the late-1980s and early 1990s. Law enforcement leaders must confidently stand by their officers when they engage in these proactive policing strategies. Likewise, law enforcement officers and command staff need to re-engage with proactive police work to fulfill the oaths they took to serve and protect their communities.

Table 3. Drivers in Fatal Motor Vehicle Crashes in the U.S., 1992–2020

Data Source: Department of Transportation

Conclusion

The “defund the police” movement of political activists and politicians, and the resulting de-policing movement on the part of many (but not all) officers, is having a real impact on the lives of the people of this nation. More people are being violently victimized each year in the U.S., and more people are being killed in traffic crashes. Criminals feel emboldened with the belief that there will be few consequences for their illegal actions.

We realize that prosecutors, judges, legislators and community leaders also need to be included in this conversation. In the coming weeks and months, we will be issuing additional articles that will review the scientific evidence that specific types of proactive policing strategies reduce crime and traffic fatalities. We believe these articles will be helpful to those trying to convince their local political leaders about the facts regarding proactive policing. In the meantime, however, we need to be getting back to improving public safety, which always starts with law enforcement.

About the Authors

Richard R. Johnson, Ph.D.

Richard R. Johnson, PhD, is a trainer and researcher with Dolan Consulting Group. He has decades of experience teaching and training on various topics associated with criminal justice, and has conducted research on a variety of topics related to crime and law enforcement. He holds a bachelor’s degree in public administration and criminal justice from the School of Public and Environmental Affairs (SPEA) at Indiana University, with a minor in social psychology. He possesses a master’s degree in criminology from Indiana State University. He earned his doctorate in criminal justice from the School of Criminal Justice at the University of Cincinnati with concentrations in policing and criminal justice administration.

Dr. Johnson has published more than 50 articles on various criminal justice topics in academic research journals, including Justice Quarterly, Crime & Delinquency, Criminal Justice & Behavior, Journal of Criminal Justice, and Police Quarterly. He has also published more than a dozen articles in law enforcement trade journals such as the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, Police Chief, Law & Order, National Sheriff, and Ohio Police Chief. His research has primarily focused on police-citizen interactions, justice system responses to domestic violence, and issues of police administration and management. Dr. Johnson retired as a full professor of criminal justice at the University of Toledo in 2016.

Prior to his academic career, Dr. Johnson served several years working within the criminal justice system. He served as a trooper with the Indiana State Police, working uniformed patrol in Northwest Indiana. He served as a criminal investigator with the Kane County State’s Attorney Office in Illinois, where he investigated domestic violence and child sexual assault cases. He served as an intensive probation officer for felony domestic violence offenders with the Illinois 16th Judicial Circuit. Dr. Johnson is also a proud military veteran having served as a military police officer with the U.S. Air Force and Air National Guard, including active duty service after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Before that, he served as an infantry soldier and field medic in the U.S. Army and Army National Guard.

His training courses include Getting Back to Work: Evidence-Based Methods for Motivating Field Personnel Productivity, Reporting Accurate Traffic Stop Data: Evidence-Based Best Practices , and Safe Places: Protecting Places of Worship from Violence and Crime.

Chief Harry P. Dolan (Ret.)

Harry P. Dolan is a 32-year police veteran who served as a Chief of Police since 1987. As one of the nation’s most experienced police chiefs, he brings 25 years of public safety executive experience to Dolan Consulting Group. He retired in October 2012 as Chief of Police of the Raleigh (N.C.) Police Department, an agency comprised of nearly 900 employees in America’s 42nd largest city.

Chief Dolan began his law enforcement career in 1980 as a deputy sheriff in Asheville, North Carolina and served there until early 1982, when he joined the Raleigh Police Department, where he served as a patrol officer. In 1987, he was appointed Chief of Police for the N.C. Department of Human Resources Police Department, located in Black Mountain. He served as Chief of Police in Lumberton, N.C. from 1992 until 1998, when he became Chief of Police of the Grand Rapids, Michigan Police Department. He served in that capacity for nearly ten years before becoming Chief of the Raleigh Police Department in September 2007. As Chief, he raised the bar at every organization and left each in a better position to both achieve and sustain success.

Harry Dolan has lectured throughout the United States and has trained thousands of public safety professionals in the fields of Leadership & Management, Communications Skills, and Community Policing. Past participants have consistently described Chief Dolan’s presentations as career changing, characterized by his sense of humor and unique ability to maintain participants’ interest throughout his training sessions. Chief Dolan’s demonstrated ability to connect with his clientele and deliver insightful instruction all with uncompromising principles will be of tremendous value in the private sector.

Chief Dolan’s unbridled passion to achieve service-excellence is a driving force behind Dolan Consulting Group. He is a graduate of Western Carolina University and holds a Master’s Degree in Organizational Leadership and Management from the University of North Carolina at Pembroke.

His training courses include Getting Back to Work: Evidence-Based Methods for Motivating Field Personnel Productivity, Verbal De-escalation Training: Surviving Verbal Conflict®, Verbal De-escalation Train The Trainer Program: Surviving Verbal Conflict®, Community Policing Training, Taking the Lead: Courageous Leadership for Today’s Public Safety, and Street Sergeant®: Evidence-Based First-Line Supervision Training.

References

[i] Shjarback, John A., David C. Pyrooz, Scott E. Wolfe, & Scott H. Decker. (2017). De-policing and crime in the wake of Ferguson: Racialized changes in the quantity and quality of policing among Missouri police departments. Journal of Criminal Justice, 50, 42-52; Powell, Zachary A. (2022). De-policing, police stops, and crime. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice, 1-20.

[ii] Dunn, Alison. “After pause, state prison system to accept new inmates.” The Toledo Blade, May 18, 2020; Provance, Jim. “DeWine bucks parole board, grants early prison release.” The Toledo Blade, April 17, 2020.; Hamilton County Reporter Staff (2020, March 19). “County circuit, superior courts declare emergency operations.” Hamilton County Reporter.

[iii] Sherman, Lawrence W., Denise Gottfredson, Doris MacKenzie, John Eck, Peter Reuter, & Shawn Bushway. (1997). Preventing Crime: What Works, What Doesn’t, What’s Promising: A Report to the United States Congress. Washington, DC; U.S. Department of Justice; Weisburd, David & John E. Eck (2004). What Can Police Do to Reduce Crime, Disorder, and Fear? The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 593(1), 42–65.

[iv] Brenan, Megan. (2022, October 28). Record-High 56% in U.S. Perceive Local Crime Has Increased. Omaha, NE: Gallup Inc. Retrieved from: https://news.gallup.com/poll/404048/record-high-perceive-local-crime-increased.aspx

[v] Schneider, Elena. (2022, October 5). Midterm Voters Key in on Crime. Politico. Retrieved from: https://www.politico.com/news/2022/10/05/midterm-voters-crime-guns-00060393

[vi] Moore, Tina & Jorge Fitz-Gibbon (2022, December 29). Teen-on-Teen Crime Part of Troubling Spike in NYC Youth Violence. New York Post. McColgan, Flint. (2023, January 3). Boston’s Overall Crime Rate is Down 1.5% in 2022, But Fatal Shootings Rose By 8 Over 2021. Boston Herald.