Extensive research has shown that citizen satisfaction with the police is influenced by their perceptions about neighborhood crime and disorder. Numerous studies have found that citizens had lower overall satisfaction and confidence in the police when they had higher levels of fear of crime in their neighborhood and higher perceptions of neighborhood disorder (such as trash, graffiti, abandoned cars, loud music, loitering homeless people, etc.). Perceptions of crime, however, do not always match actual levels of crime. For example, according to the FBI Uniform Crime Reports, both property and violent crime declined steadily from the 1990s through 2013.1 National survey data from the Gallup organization, however, reveals that fear of crime among Americans steadily increased during the same period.2 While actual crime has decreased, perception of the amount of crime increased.

Another important point to keep in mind is that policing tactics that decrease actual crime may not reduce fear of crime. Extensive research has found that specific policing tactics such as intelligence-led directed patrols, crime prevention by environmental design, nuisance abatement activities, targeting repeat offenders, and other problem-oriented policing strategies are very effective at reducing actual crime, but many of these tactics have no effect on fear of crime or citizen satisfaction with the police.3 Actual crime and perceptions of crime are two separate issues that often need different policing tactics. This research brief will address the available evidence on what law enforcement agencies, and their officers, can do to reduce citizen fears about crime and disorder in local neighborhoods, thereby increasing local citizen satisfaction with the police.

What Reduces Fear of Crime?

Criminal justice researchers Jihong Zhao of Sam Houston State University, Matthew Scheider of the U.S. Department of Justice, and Quint Thurman of the University of the Southwest sought out every published research study of policing tactics in the U.S. that measured whether or not certain police activities reduced citizen fear of crime. They were able to locate 31 such studies published before 2002, many of which examined multiple types of policing activities. They found that almost all of these studies also measured citizen satisfaction with the police before and after implementing changes in policing activities.4 From these studies they were able to determine what kinds of policing tactics reduced fear of crime and increased citizen satisfaction with the police.

These studies revealed that most of the problem-oriented policing strategies that have been so effective at reducing actual crime did not reduce fear of crime, and sometimes even increased fear of crime. For example, when an area is flooded with extra patrol cars aggressively making stops and searching for weapons, the increased police presence makes some citizens perceive the area as dangerous when they had not thought so before. Three policing activities, however, repeatedly showed evidence of reducing fear of crime and increasing citizen satisfaction with the police. These three strategies were police sub-stations, community meetings, and non-enforcement, face-to-face contact between officers and citizens in the neighborhoods of greatest need.5

Dr. Zhao and his colleagues found ten studies that dealt with the implementation of a police substation within a strip mall, housing project, or community center. Some of the substations studied were staffed only by officers, and others by a mixture of officers and civilian personnel. Some substations were operated 24-hours a day, others were only open during the day or evening shift, and a few were manned only a few days and times each week. In every case, the presence of a substation in the neighborhood reduced fear of crime among neighborhood residents. In two-thirds of the studies, the presence of a substation increased citizen satisfaction with the police among neighborhood residents as well.6

Dr. Zhao and his colleagues examined thirteen studies of community meetings of various sorts. Some were neighborhood watch meetings and some were “town hall” style meetings where citizens came to state their grievances with the police, both of which had an impact on reducing fear of crime and increasing satisfaction with the police. The greatest impact on fear of crime and citizen satisfaction, however, came from community problem-solving meetings. This type of meeting involves inviting residents of a specific neighborhood or apartment complex to meet, receive instruction in the S.A.R.A. model of problem-oriented policing, and then work in small groups with officers to identify and develop strategies addressing specific crime problems that were of concern to the residents. The interactions between the citizens and officers in these problem-solving meetings open the eyes of citizens to the realities and difficulties police officers face, but also reveal to officers unknown or untapped community resources available to assist them. All of the studies of community problem-oriented meetings with citizens found that they reduced fear of crime among the participants and increased their satisfaction with the police.7

Dr. Zhao and his colleagues also reviewed ten studies that tested proactive, non-enforcement citizen contacts. These contacts were not public relations fluff, but rather real police work activities focused on maintaining order, detecting crime, and making citizens feel safe.8 For example, in one study the Houston Police Department targeted a couple of high crime blocks and required patrol officers to stop twice during their shift to meet residents at their homes, or business people at their stores or offices. During these brief contacts (usually less than 10 minutes), the officer would introduce him or herself, say the purpose of the visit was simply to get acquainted and learn whether there were any problems in the area the citizen felt the police should know about. The officer then left a business card. For each contact, the officer completed a citizen contact card listing the citizen’s name, address, phone number, and any problems discussed. Neighborhood citizen satisfaction surveys that were conducted before and after officers were ordered to make these contacts revealed that fear of crime fell substantially in the neighborhoods targeted, and citizen satisfaction with the police rose.9

All ten studies of proactive interactions with average citizens found decreases in fear of crime and increases in citizen satisfaction with the police.10 Some of the studies, like the one in Houston, involved officers being given a quota of two interactions per shift, but were also given the discretion to decide where and with whom to conduct these contacts. Other studies involved situations where officers were assigned specific addresses at which they were to conduct their contacts. While attending a Bureau of Justice Administration conference last summer, I learned that the Portland Bureau of Police in Oregon had mated this strategy with its intelligence- led policing efforts. On their department, a computer, through the computer-aided dispatch system, assigns officers to conduct these non-enforcement contacts at specific crime hot spot locations at specific hot crime times. Regardless of the method, the same positive outcomes result.

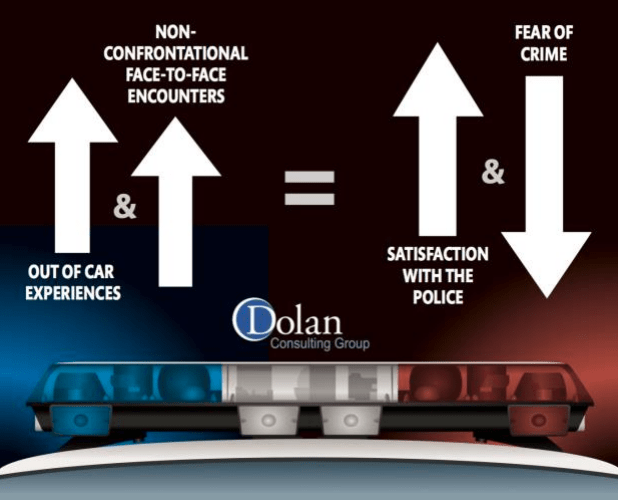

What do these three strategies – community substations, community problem-solving meetings, and proactive non-enforcement contacts – have in common? All three tactics increase the quantity and quality of face-to-face non-enforcement interactions between police officers and community members in the areas of greatest need of police services. All three of these tactics create situations in which people living in areas of greatest need get to know officers by name and the officers get to know the many good (but apprehensive or fearful) citizens of the neighborhoods they patrol. Too much police-citizen interaction involves the 10% of society that causes trouble for the remaining 90% of the people. We need to increase non-hostile interactions with that 90% of the community.

Are there Newer Studies?

Some might criticize the research Dr. Zhao and his colleagues reviewed as being too old. There are two responses to this argument. First, there is abundant research evidence that human behavior does not change much from century to century, much less from decade to decade. Second, there is more recent research that continues to support the findings of Dr. Zhao and his colleagues.

One study published in 2016 involved showing citizens a photograph of a city street scene and asking them to complete a short survey about how fearful they would be about walking down the street.11 Of the 352 people in the study, some were shown a version of the street scene with foot patrol police officers present, others were shown a version with police cars on the street, and others were shown versions with no police presence visible. The people who were shown the version with the foot patrol officers indicated they were least fearful of walking down the street. However, those who were shown the version with the two police cars on the street were the most fearful of walking down the street. In other words, when they saw two officers walking in the area they were less fearful, but when they saw two patrol cars they were more fearful than if there had been no police presence at all.

Think about that from your own personal experience. When you are out of your jurisdiction and out of uniform, do you feel more comfortable approaching a uniformed officer who is standing in line at a fast food restaurant, or an officer sitting in his patrol car in a vacant parking lot? When on duty, are you more at ease when people approach you when you are inside or outside of your patrol vehicle? Apparently there is something going on psychologically for both the officer and the citizen regarding the patrol vehicle.

In another study, researchers surveyed 977 residents of apartments in one large city. The survey contained questions about a variety of different city services, but included questions about fear of crime, satisfaction with the police. These residents were surveyed about how often they saw police cars, foot patrols, or had informal face-to-face contact with police officers. The residents who reported having had informal face-to-face contact with the police in the last six months had the lowest fear of crime and the highest satisfaction with the police, followed by those who had seen foot patrols. Having seen police cars in the neighborhood had no influence on fear of crime or satisfaction with the police.12

A final study from England assigned foot patrol officers or civilian police volunteers to patrol crime hot spot locations at peak times for crimes to occur. Like the officers in Houston described earlier, these officers approached citizens, introduced themselves, and asked if there were any crime or disorder problems needing their attention. These officers averaged only 21 minutes at each hot spot location but they ended up significantly reducing citizen fear of crime and increasing general public satisfaction with the police. Because they were a police presence targeted at hot spot locations and times, they also reduced reported crimes at these hot spots by 39%, and reduced emergency calls for service by 20%.13

Conclusion

Remember that the tactics that reduce actual crime have little impact on fear of crime and citizen satisfaction with the police. Citizen perceptions of crime and the police are unrelated to actual crime rates. One thing that law enforcement agencies can do to improve citizen satisfaction and confidence in the police is to help reduce citizen fear of crime, especially in the neighborhoods of most need. Research has revealed that the most effective tactics law enforcement agencies can implement to reduce citizen fear of crime, and increase citizen satisfaction with the police, involve non-confrontational, face-to-face interaction between officers and average citizens in the neighborhoods of greatest need of police services. Proactive non-enforcement citizen contacts, community problem-solving meetings, and interactions through neighborhood substations are three examples of tactics that lower fear and increase satisfaction with the police.

This is really the type of policing that goes on every day in small town police departments all across the nation. In small towns and villages, the residents usually know their officers by name and vice versa, with several personal friendships existing between the two. Officers hear concerns from residents almost daily and often develop solutions in cooperation with the reporting residents. The police station is usually within walking distance to everyone in town and the door is always open. Some residents even routinely stop by the station just to visit.14 Perhaps through increasing non-enforcement, face-to-face official police contacts between officers and average citizens, we can move closer to this ideal in every community.

References

1 Worrall, J. (2014). Crime Control in America. Boston, MA: Pearson.

2 Ibid.

3 Hoover, L. T. (2014). Police Crime Control Strategies. Clifton Park, NY: Cengage.

4 Zhao, J., Scheider, M., & Thurman, Q. (2002). The effect of police presence on public fear reduction and satisfaction: a review of the literature. The

Justice Professional, 15(3), 273- 299.

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 Brown, L., & Wycoff, M. A. (1987). Policing Houston: reducing fear and improving service. Crime and Delinquency, 33(1), 71-89.

10 Zhao, J., Scheider, M., & Thurman, Q. (2002).

11 Doyle, M., Frognar, L., Andershed, H., & Andershed, A. (2016). Feelings of safety in the presence of the police, security guards, and police volunteers. European Journal of

Criminal Policy and Research, 22(1), 19-40.

12 Salmi, S., Gronroos, M., & Kreskinen, E. (2004). The role of police visibility in fear of crime. Policing: IJPSM, 27(4), 573-591.

13 Arien, B., Weinborn, C. & Sherman, L. W. (2016). “Soft policing” at hot spots: do police community support officers work? A randomized, controlled trial. Journal of

Experimental Criminology.

14 Weisheit, R. A., Falcone, D. A., & Wells, L. E. (2005). Crime and Policing in Rural and Small-Town America. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press.