As part of the ongoing national conversation around police reform, many are calling for a college degree requirement for officers in agencies and states where such a requirement does not currently exist. These calls reflect a widespread belief that a university education is likely to result in improved conduct by law enforcement officers.

But is there any evidence that this belief is true? There has actually been a significant amount of social science research devoted to measuring whether college-educated officers perform differently than officers who lack a college degree. In fact, almost every study of police behavior has included officer education level as a control variable. So, what have we learned?

Does Higher Education Mean Higher Standards of Conduct?

In 2000, the National Research Council of the National Academies was charged by Congress to review and summarize all of the existing research on policing within the United States. They convened a committee of eighteen policing scholars from the academic fields of criminal justice, criminology, law, sociology, political science and public administration who spent four years pouring over all of the existing published research about policing. Regarding the topic of the influence of education on officer performance, the committee reviewed more than 30 published studies between 1960 and 2000 that had examined such officer behaviors as arrest, use of force and citizen complaints.[1]

After reviewing all of these studies, the committee reported the following: “The evidence reviewed by the committee does not permit conclusions regarding the impact of education on officer decision making.” The committee came to this conclusion because all of the research they reviewed provided inconsistent results. For example, while one study revealed officers with a college degree used less force than officers without a college degree, the next study they reviewed found there was no difference between the two in terms of use of force.[2]

Since 2000, there have been more research studies published that have measured the impact of college education on officer behavior. But the findings are still inconclusive with respect to the impact, if any, of a college education on officer behavior.

We examined a number of studies published since 2000 to illustrate this point. We found two studies on officer traffic enforcement behavior (i.e., how proactively they stop and cite motorists) that included a measure of officer education level. One study found a college degree had no impact,[3] while the other found that officers without a college degree engage in more proactive enforcement.[4] Another study examined criminal arrest productivity and found no difference between college-educated officers and those without a bachelor’s degree.[5] And a fourth study examined how often officers proactively searched citizens and found no difference between officers with or without a bachelor’s degree.[6]

Two studies measured officers’ organizational commitment,[7] and found officer education level had no impact. Three studies measured officer job satisfaction, with one finding college-educated officers had lower job satisfaction than officers without a degree[8] and two finding college degree had no impact on satisfaction.[9] One study examined officer seatbelt usage while on duty[10] and another measured officer openness to de-escalation training.[11] Both of these studies found that whether or not the officer had a college degree had no impact. Two more studies examined officers’ voluntary engagement in community policing activities and both found that a college degree made no difference.[12]

Regarding use of force, we found six studies that compared the frequency of use of force between officers with and without a bachelor’s degree. Four of the studies found that officers with at least a bachelor’s degree used force less often than officers with less than a bachelor’s degree.[13] However, two of the studies found no difference between officers with or without a bachelor’s degree in their rates of use of force.[14] Regarding citizen-generated or internal complaints of misconduct, six studies examined if the officer’s education level was associated with reports of misconduct. Four of the studies found that whether or not an officer had a bachelor’s degree was unrelated to how many misconduct allegations the officer received,[15] yet two studies found that officers with a bachelor’s degree received fewer allegations of misconduct.[16]

Why the Inconsistencies?

Why are these results so inconsistent? Many scholars have pointed to the difficulty in defining or quantifying “college education”. In most studies, “college education” is measured as whether or not the officer has a bachelor’s degree, but education is much more complex than that. Is the officer who is ten credit hours short of graduating different from the officer who completed her degree? What about grades? Does the officer who graduated by the skin of his teeth and after taking a few failed courses over again have the same education as the officer who completed his degree with a perfect 4.0 grade point average? Is a graduate from a school with low academic standards just as educated as a student who graduated from an Ivy League or flagship state university?[17]

What about one’s major or the type of curriculum studied? Does a degree in chemistry or graphic design better prepare an individual to become a successful law enforcement officer? Is a degree in psychology or communications better preparation for a career in law enforcement than a degree in criminology or criminal justice?

Even among criminal justice and criminology programs, the focus and the material taught varies tremendously. At most four-year universities, criminology/criminal justice course content is strongly grounded in sociology (emphasizing social theories related to issues of race, class and gender), and the majority of the faculty are individuals who hold doctorates but have never worked a day in the criminal justice system. Some have never even held a full time job in any realm before becoming a professor.[18]

However, in a few university programs around the nation, and at most community colleges, the overwhelming majority of the faculty are former law enforcement and correctional officers, and the course work is more vocational in nature.[19] Some of these programs even offer police academy certification. Are the students who emerge from these two models of criminal justice education equally equipped for (or even interested in) a law enforcement career?

Why Is College So Important?

Why would we think that a college education would make an individual a better law enforcement officer? There are many assertions behind this idea that law enforcement officers should be college educated. One is the belief that a college education develops valuable knowledge, skill and ethics within the individual. It is argued that a college education improves one’s capacity to critically analyze problems, communicate verbally and in writing and develop greater sensitivity to other cultures and beliefs.[20]

It is debatable whether all types of college education experiences actually develop these skills in graduates. But even if it does, the empirical evidence reveals that the influence of a college education on an officer’s work behavior are, at best, mixed. For more than sixty years now, the empirical research has failed to show the sorts of dramatic differences in officer behavior that many police reformers had hoped to see.

More and more Americans are also questioning the value of a college degree in general. College and university enrollments in the U.S. have been in steep decline since 2019. Between 2019 and 2020, before the pandemic struck, undergraduate enrollments in the U.S. fell by 3.1%, which amounts to more than 600,000 students electing to forgo college. From 2020 to 2021, undergraduate enrollments fell a further 4.6%, and from 2021 to 2022 they fell another 4.7%. That is a 12.4% decrease across the last three years. Community colleges were hit even harder, declining 10.6% in enrollments from 2020 to 2021, and decreasing 7.8% from 2021 to 2022.[21]

Several recent studies have sought to determine the reasons for the declining interest in college. Surveys of current, former and potential college students have revealed that there are a number of common reasons for taking a pass on going to college. These reasons include the belief that college degrees are no longer a guarantee of getting a good-paying job. Many point to a growing number of alternative, low-cost ways to learn new skills and information on their own. Others surveyed believe that the information learned in college today is often irrelevant to the actual work world. Many believe that exposure to actual work practices is more valuable than classroom learning in many occupations. For some, the rising cost of education makes college inaccessible without going deep into debt with student loans.[22] Finally, some see college as a hostile environment for individuals who hold centrist or conservative political or religious views.[23] Regardless of the reasons, there are simply fewer and fewer college graduates available to attract to the law enforcement profession.

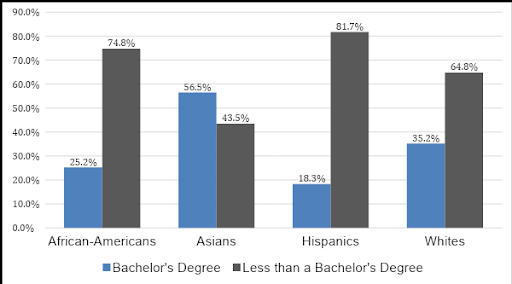

Even before these recent declines, college education was not evenly distributed across ethnic and racial groups. In 2018, only 43.5% of Asian adults and 64.8% White adults lacked a four-year college degree. However, 74.8% of African-American adults and 81.7% of Hispanic adults lacked a four-year degree.[24] Requiring a college degree for entry into a career field severely limits the number of qualified African-American and Hispanic-American applicants as agencies across the country already struggle to recruit and retain officers who reflect the racial diversity of the communities that they serve.

Table 1. U.S. College Education Distribution by Race / Ethnicity

Source: 2018 Census Data

Conclusion

During this period in law enforcement history, when the profession is struggling to attract enough qualified candidates to fill officer vacancies across the nation, does it make sense to limit the pool of potential applicants even further by requiring applicants to have a college degree? Six decades of empirical research has failed to reveal any evidence that college-educated officers behave significantly differently than non-college-educated officers. What the student learns and how much the student grows as an individual varies dramatically from student to student, major to major, and college to college. Fewer and fewer young Americans are pursuing a college education—even at the community college level—so the number of college graduates available to recruit is dwindling. So it might not be wise to require any level of college education as a prerequisite to apply.

What is likely a better strategy is to simply look for the qualities in the individual that some seem to believe a college education fosters. Your agency may have been hoping that a college education requirement would attract applicants who possess valuable knowledge, skills, ethics, a capacity to critically analyze problems, an ability to communicate verbally and in writing, and sensitivity to other cultures and beliefs. Instead of requiring a college degree, your agency could utilize assessment centers with written tests, role-play scenarios and interviews to detect these characteristics in applicants, no matter their level of formal education. It may also make sense to carefully screen for these attributes in the background investigation, academy and field training phases of the hiring process.

As there is no firm evidence that a college education makes an individual a dedicated and outstanding law enforcement officer, agencies that adopt this requirement are likely to miss out on many excellent candidates by excluding them completely from their pool of applicants at a time when so many agencies are already facing historically significant recruiting challenges.

Before excluding a massive number of otherwise qualified and competent applicants, one should be fairly certain that the requirement in question is demonstrably relevant to a successful career in law enforcement. When it comes to the requirement of a college degree, the evidence is far from compelling. And the mere fact that many officers throughout the country prove themselves to be outstanding assets to their agencies and communities–in spite of the fact that they never received a college degree–serves as compelling evidence that the college requirement is unnecessary.

About the Authors

Richard R. Johnson, Ph.D.

Richard R. Johnson, PhD, is a trainer and researcher with Dolan Consulting Group. He has decades of experience teaching and training on various topics associated with criminal justice, and has conducted research on a variety of topics related to crime and law enforcement. He holds a bachelor’s degree in public administration and criminal justice from the School of Public and Environmental Affairs (SPEA) at Indiana University, with a minor in social psychology. He possesses a master’s degree in criminology from Indiana State University. He earned his doctorate in criminal justice from the School of Criminal Justice at the University of Cincinnati with concentrations in policing and criminal justice administration.

Dr. Johnson has published more than 50 articles on various criminal justice topics in academic research journals, including Justice Quarterly, Crime & Delinquency, Criminal Justice & Behavior, Journal of Criminal Justice, and Police Quarterly. He has also published more than a dozen articles in law enforcement trade journals such as the FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, Police Chief, Law & Order, National Sheriff, and Ohio Police Chief. His research has primarily focused on police-citizen interactions, justice system responses to domestic violence, and issues of police administration and management. Dr. Johnson retired as a full professor of criminal justice at the University of Toledo in 2016.

Prior to his academic career, Dr. Johnson served several years working within the criminal justice system. He served as a trooper with the Indiana State Police, working uniformed patrol in Northwest Indiana. He served as a criminal investigator with the Kane County State’s Attorney Office in Illinois, where he investigated domestic violence and child sexual assault cases. He served as an intensive probation officer for felony domestic violence offenders with the Illinois 16th Judicial Circuit. Dr. Johnson is also a proud military veteran having served as a military police officer with the U.S. Air Force and Air National Guard, including active duty service after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. Before that, he served as an infantry soldier and field medic in the U.S. Army and Army National Guard.

Matt Dolan, J.D.

Matt Dolan is a licensed attorney who specializes in training and advising public safety agencies in matters of legal liability, risk management and ethical leadership. His training focuses on helping agency leaders create ethically and legally sound policies and procedures as a proactive means of minimizing liability and maximizing agency effectiveness.

A member of a law enforcement family dating back three generations, he serves as both Director and Public Safety Instructor with Dolan Consulting Group.

His training courses include Recruiting and Hiring for Law Enforcement, Confronting the Toxic Officer, Performance Evaluations for Public Safety, Making Discipline Stick®, Supervisor Liability for Public Safety, Confronting Bias in Law Enforcement and Internal Affairs Investigations: Legal Liability and Best Practices.

Disclaimer: This article is not intended to constitute legal advice on a specific case. The information herein is presented for informational purposes only. Individual legal cases should be referred to proper legal counsel.

References

[1] National Research Council of the National Academies (2004). Fairness and Effectiveness in Policing: The Evidence. Washington, DC: National Research Council of the Academies.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Johnson, R. R. (2011). Officer attitudes, management influences, and police work productivity. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 36(4), 293-306.

[4] Kennedy, S. M. (2022). Police Education and its Influence on Traffic Enforcement Performance. Lynchburg, VA: Master’s Thesis: Liberty University.

[5] Rydberg, J., & Terrill, W. (2010). The effect of higher education on police behavior. Police Quarterly, 13(1), 92-120.

[6] Rydberg, J., & Terrill, W. (2010). The effect of higher education on police behavior. Police Quarterly, 13(1), 92-120.

[7] Johnson, R. R. (2015). Supervisor feedback, perceived organizational support, and organizational commitment among police officers. Crime and Delinquency, 61(9), 1155-1180; Rief, R. M., & Clinkinbeard, S. S. (2020). Exploring gendered environments in policing: workplace incivilities and fit perceptions in men and women officers. Police Quarterly, 23(4), 427-450.

[8] Ingram, J. R., & Lee, S. U. (2015). The effect of first-line supervision on patrol officer job satisfaction. Police Quarterly, 18(2), 193-219.

[9] Brady, P. Q., & King, W. R. (2018). Brass satisfaction: Identifying the personal and work-related factors associated with job satisfaction among police chiefs. Police Quarterly, 21(2), 250-277; Johnson, R. R. (2012). Police officer job satisfaction; a multidimensional analysis. Police Quarterly, 15(2), 157-176.

[10] Wolfe, S., Lawson, S. G., Rojek, J., & Alpert, G. (2020). Predicting police officer seat belt use: evidence-based solutions to improve officer driving safety. Police Quarterly, 23(4), 472-499.

[11] Smith, M. R., Engel, R. S., Isaza, G. T., & Motz, R. T. (2022). De-escalation training receptivity and first-line police supervision: findings from the Louisville Metro Police Study. Police Quarterly, 25(2), 201-227.

[12] DeJong, C., Mastrofski, S. D., & Parks, R. B. (2001). Patrol officers and problem-solving: an application of expectancy theory. Justice Quarterly, 18(1), 31-61; Engel, R. S., & Worden, R. E. (2003). Police officers’ attitudes, behavior, and supervisory influences: an analysis of problem solving. Criminology, 41(1), 131-166.

[13] Donner, C. M., Maskaly, J., Piquero, A. R., & Jennings, W. G. (2017). Quick on the draw: assessing the relationship between low self-control and officer-involved police shootings. Police Quarterly, 20(2), 213-234; McElvain, J. P., & Kposowa, A. J. (2008). Police officer characteristics and the likelihood of using deadly force. Criminal Justice & Behavior, 35(4), 505-521; Paoline, E. A., & Terrill, W. (2007). Police education, experience, and the use of force. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34(2), 179-196; Rydberg, J., & Terrill, W. (2010). The effect of higher education on police behavior. Police Quarterly, 13(1), 92-120.

[14] Ingram, J. R., Terrill, W., & Paoline, E. (2018). Police culture and officer behavior: application of a multi-level framework. Criminology, 56(4), 780-811; Paoline, E. A., Terrill, W., & Somers, L. J. (2021). Police officer use of force mindset and street-level behavior. Police Quarterly, 24(4), 547-577.

[15] Brandl, S. G., Stroshine, M. S., & Frank, J. (2001). Who are the complaint-prone officers? Journal of Criminal Justice, 29(6), 521-529; Ingram, J. R., Terrill, W., & Paoline, E. (2018). Police culture and officer behavior: application of a multi-level framework. Criminology, 56(4), 780-811; Paoline, E. A., & Terrill, W. (2007). Police education, experience, and the use of force. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34(2), 179-196; Terrill, W., & Ingram, J. R. (2016). Citizen complaints against the police: an eight city examination. Police Quarterly, 19(2), 150-179.

[16] Harris, C. J. (2010). Problem officers? Analyzing problem behavior patterns from a large cohort. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38(2), 216-225; Manis, J. Archbold, C., & Hassell, K. D. (2008). Exploring the impact of police officer education level on allegations of police misconduct. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 10(4), 509-523.

[17] Manis, J. Archbold, C., & Hassell, K. D. (2008). Exploring the impact of police officer education level on allegations of police misconduct. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 10(4), 509-523.

[18] Cooper, J. A., Walsh, A., & Ellis, L. (2010). Is criminology moving toward a paradigm shift? Evidence from a survey of the American Society of Criminology. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 21(3), 332-347; Wright, J. P., & DeLisi, M. (2015). Conservative Criminology: A Call to Restore Balance to the Social Sciences. New York: Routledge.

[19] Castellano, T. C., & Schafer, J. A. (2005). Continuity and discontinuity in competing models of criminal justice education: Evidence from Illinois. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 16(1), 60-78; Cordner, G. (2016). The unfortunate demise of police education. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 27(4), 485-496.

[20] Baro, A. L., & Burlingame, D. (1999). Law enforcement and higher education: Is there in impasse? Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 10(1), 57-73; Cordner, G. (2016). The unfortunate demise of police education. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 27(4), 485-496; Shernock, S. K. (1992). The effects of college education on professional attitudes among police. Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 3(1), 71-92.

[21] Neitzel, M. T. (2022, May 26). New report: the college enrollment decline worsened this spring. Forbes. Downloaded from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/michaeltnietzel/2022/05/26/new-report-the-college-enrollment-decline-has-worsened-this-spring/?sh=6417839624e0

[22] ECMC Group LLC (2022). Report: Gen Z Teens Want Shorter, More Affordable, Career-Connected Education Pathways. Minneapolis, MN: ECMC Group LLC.

[23] Dodge, S. (2022, April 26). While other schools struggle, Hillsdale College enrollment has surged during COVID-19. Here’s why. MLive. Downloaded from: https://www.mlive.com/news/jackson/2022/04/hillsdale-college-enrollment-surged-during-covid-19-heres-why.html; Jesse, D. (2021, October 8). Why some small conservative Christian colleges see growth where other schools see declines. The Detroit Free Press. Downloaded from: https://www.freep.com/in-depth/news/education/2021/10/08/conservative-christian-colleges-grow/7396185002/

[24] Statistica Inc. (2019). Percentage of Educational Attainment in the United States in 2018, by Ethnicity. New York: Statistica Inc.