Many law enforcement agencies across the nation have recently reported increasing difficulty in recruiting well-qualified individuals to serve as law enforcement officers. Their recruiting efforts are often targeted at criminal justice students in college, and military veterans. While there is nothing wrong with utilizing these two pipelines for qualified applicants, the fact that these methods are not producing the needed results points to the necessity to change the way law enforcement agencies recruit. This means moving beyond the handful of job fairs that recruiters traditionally attend and casting a wider net.

Are there other fields that contain a high proportion of individuals who also might be interested in a career in law enforcement, but have never taken the time to explore the profession? What career fields might be attracting some of the very same applicants that law enforcement agencies should be recruiting?

In order to explore this question, and many others related to recruiting and hiring for law enforcement, Dolan Consulting Group (DCG) surveyed 1,673 current law enforcement officers from across the nation. We asked them to think back to when they were applying to become a law enforcement officer for the first time. We asked them to imagine they had been blocked from becoming a law enforcement officer for some reason, such as a vision or another health issue. We asked them to tell us what other occupation or career field they would have pursued instead of law enforcement. We did this to explore if there were any common alternative career choices that were revealed among current law enforcement officers. If so, this would suggest these career fields contain individuals who may be interested in police work—individuals who might be swayed to consider a law enforcement career if they knew more about the job and were invited to apply.

The Sample

All sworn law enforcement officers who attended the various training courses offered by DCG between August 2018 and March 2019 were given the opportunity to participate in our DCG Police Recruiting and Hiring Survey. A total of 1,673 sworn personnel took the survey, of which 286 (17.1%) were female and 1,387 (82.9%) were male. The racial composition of the respondents was 83.4% White (non-Hispanic), 6.8% African-American, 5.4% Hispanic, 1.4% Multiracial, 1.0% Native American, 0.4% Asian, and 1.6% all other groups. In terms of highest education level, 30.8% had less than an associate’s degree, 18.2% had an associate’s degree, and 51% had a bachelor’s degree or higher.

A total of 52.8% of the respondents held the rank of officer, deputy, or trooper, while another 10.0% held the rank of detective. Another 23.0% held first-line supervisory ranks (corporal or sergeant), 4.5% held middle-management ranks (mostly lieutenants), and the remaining 9.7% held command staff ranks (captain or higher). Approximately 65% of the respondents were assigned to the patrol division of their agency, 14% to investigations, and 14% to command administration. The remaining 7% indicated other assignments such as training, community policing unit, or media relations. These respondents came from 49 different states and agencies ranging in size from less than a dozen officers to agencies with thousands of officers.

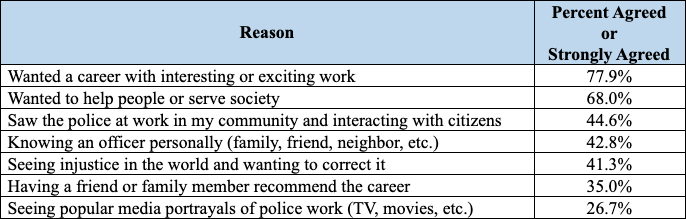

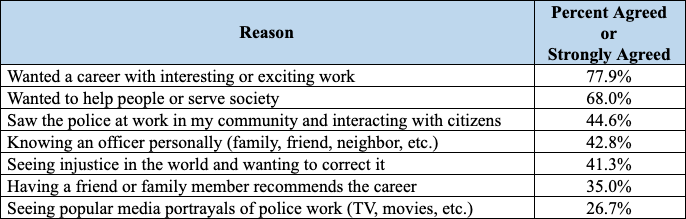

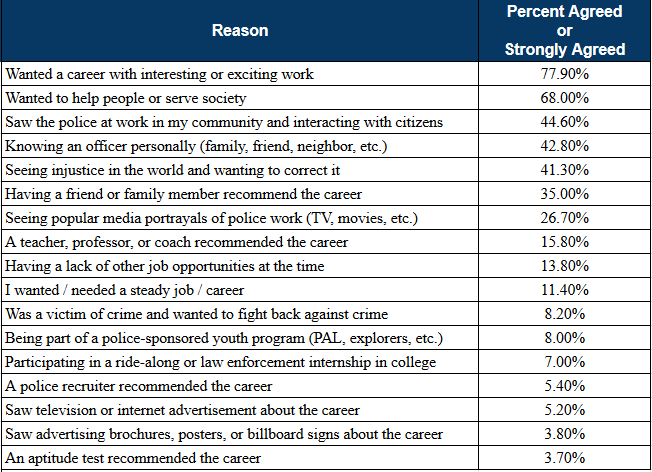

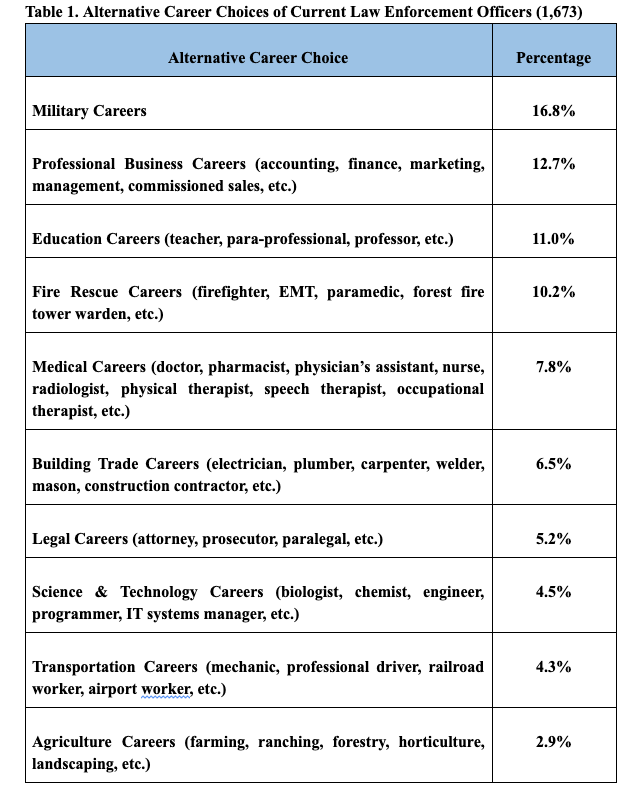

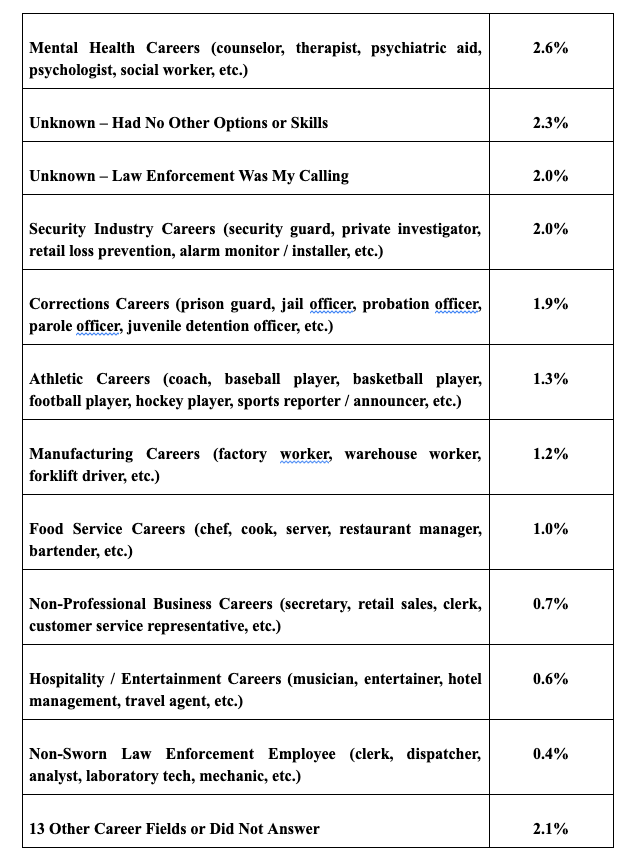

As stated earlier, we asked these individuals to share what profession or career field they would likely have pursued if the path to a law enforcement career had been blocked for some reason. The responses of the entire sample are displayed in Table 1 below. As this table reveals, there were a wide array of alternative careers disclosed. A total of 246 specific jobs were mentioned, making individual analysis more difficult. The responses were therefore grouped by career categories. For example, individuals who indicated alternative career choices of doctor, pharmacist, nurse, radiologist, physical therapist, speech therapist, and occupational therapist were all grouped into a category titled “Medical Careers.” Once these groupings were accomplished, some trends started to be revealed.

When examining the entire sample together in Table 1, it is evident that there are specific alternative careers that attract people who have made law enforcement their current career. Despite there being a total of 34 career categories, more than half of the responses were concentrated within only four categories, and three-quarters of the responses fell into the top eight categories. Military careers were the most prevalent, which is probably no surprise as, traditionally, large numbers of law enforcement officers have been veterans.

The second-most common career category, professional business careers, may be more surprising. Fire rescue careers came next, a career field closely related to law enforcement in terms of helping people and being first responders to crises. Education was the fourth most commonly selected field, with several respondents actually disclosing they left jobs they already had as teachers in order to become law enforcement officers. These four categories alone accounted for half (50.7%) of the respondents in the sample.

The fifth top-ranked category was medical professions—another career area where people seek life fulfillment by helping people. This was followed by the building trades, law, and science and technology careers. The remaining 26 career categories combined only accounted for a quarter of the respondents. These results indicate that those who select law enforcement as a career come from a wide variety of interests and backgrounds. Nevertheless, there are notable areas of career interest concentration.

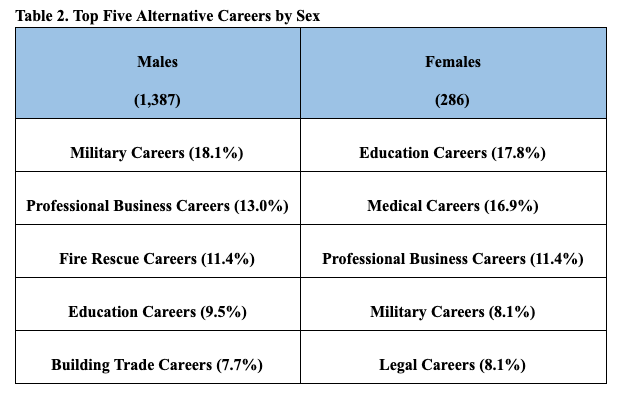

Are there Male and Female Differences?

Next, we divided the sample by sex to see if the responses were different between males and females. Females are underrepresented within the law enforcement profession and if differences were found, they might identify areas for targeting the recruitment of female candidates. As Table 2 below reveals, differences between the sexes were revealed. The top five categories selected by the male respondents accounted for roughly 60% of the male sample. The top career fields identified by the male respondents matched the top five responses for the overall sample with the exception of removal of the medical profession and the addition of the building trades.

The female responses differed in several ways. One third of the female respondents indicated that if they had not chosen a law enforcement career they would have become (or were) teachers, nurses, or medical therapists—jobs disproportionately held by women in our society. Another quarter of the female respondents identified the business world, the military, and law as their alternative career choices. Attempts to recruit more women into law enforcement should target these career areas, especially college majors and persons working in the fields of education and medicine.

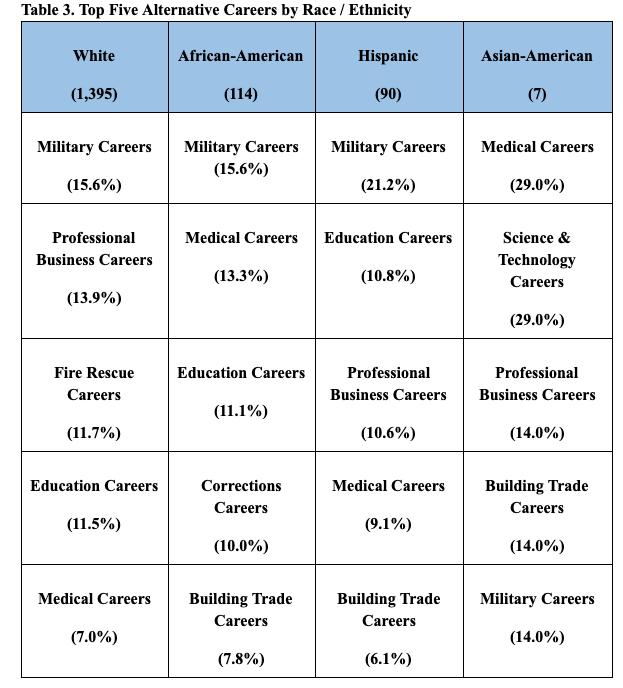

Are there Race / Ethnic Differences?

Many law enforcement agencies feel that they are under social pressure to increase the racial diversity of their organization. In order to assist efforts to recruit more qualified minority applicants, we examined the responses by race / ethnic categories. The largest category in the sample was non-Hispanic Whites (1,395 respondents). African-American and Hispanic respondent representations were large enough for analysis, being 114 and 90 respondents respectively. Only seven respondents were Asian-Americans, however, so care should be taken not to over-emphasize the results for this group. Seven individuals hardly represent the diversity of experiences / attitudes among all of the nation’s Asian-American police officers. Nevertheless, this analysis by race revealed distinct differences in responses across groups, as revealed in Table 3 below.

As Table 3 reveals, the top five categories for Whites contain about 60% of the White respondents, with more than a quarter of responses falling into military or professional business careers, followed by fire rescue, education, and medical careers. The top five alternate careers for African-Americans, however, has several differences. Despite having military careers as the most frequent response (identical to Whites at 15.6%), African-Americans were more likely than were Whites to identify education and medical careers as their alternative career options. Additionally, unlike Whites, the blue collar fields of corrections careers and the building trades were more commonly selected options by African-American officers.

The Hispanic respondents also had military careers as the most cited career alternative, however, the proportion of this group that selected the military (21.2%) was far greater than that of the other three race / ethnic groups. Hispanics also highly rated business professions, education, medical careers, and the building trades. Despite keeping in mind that the Asian-American representation was very small, it was noteworthy that the alternative career choices for two-thirds of the Asian-American officers were either medicine, science / technology, or the business professions, which differed from the responses of the other three groups.

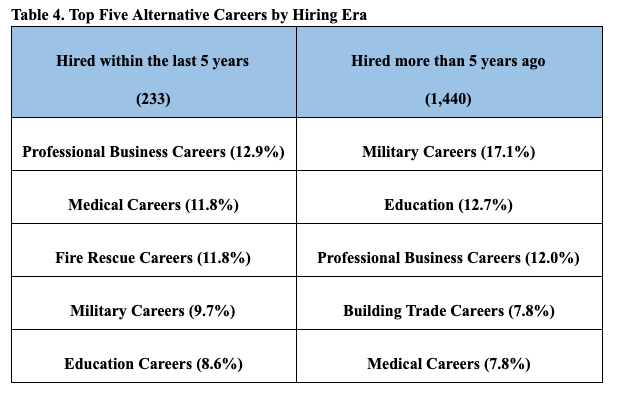

Have Things Changed Over Time?

Finally, we compared the responses of officers hired within the last five years, to those hired more than five years ago. The results, presented in Table 4 below, again suggest differences by era of hiring. A total of 233 respondents had joined the law enforcement profession within the last five years. The top five responses of these individuals reveal either societal changes over time, or economic changes, or both.

While 17.1% of those hired more than five years ago would have selected a military career as their “backup career” option, only 9.7% of those hired within the last five years would have done so. Over previous generations of law enforcement officers, the most recent generation is the least likely to have considered a military career. Instead, the most recent generation of law enforcement officers were much more interested in alternative careers in business, the medical field, or serving in the alternative first responder career of fire rescue. Furthermore, whereas 7.8% of officers from past generations of law enforcement would have selected one of the building trades, this field did not make the top five list for officers hired within the last five years.

Actionable Steps

The results of these analyses suggest several practical steps with regard to law enforcement recruiting strategies.

Reach Out to Business Professionals – Although most people would not consider the business professions to be associated with law enforcement, no matter how we analyzed the responses the business professions almost always were among the top five categories for alternative career options. Business careers such as sales, management and marketing require strong people skills, creativity and self-motivation—all skills one needs in law enforcement.

Law enforcement, however, provides additional benefits that the business professions usually do not, such as the ability to make a difference in society and greater job stability. According to 2016 data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, 20% of businesses with employees fail within the first year, 50% fail within five years, and 70% fail within ten years.[1] Some business professionals, tired of the stress of constantly changing companies, locations, and benefits plans, may welcome the stability of a career in law enforcement. Salaries within the business professions are also comparable to the law enforcement career as entry-level positions in marketing start around $40,000 today, and mid-level business managers make around $83,000 annually.[2]

Many people employed within the business world may not have an accurate view of the law enforcement profession, or the salary and benefits the career offers. Take every opportunity to inform professional business people within your community about the benefits (personal as well as material) of a law enforcement career. When a business in your area announces it is struggling, downsizing, or going out of business, approach the leadership of the business and ask for permission to make a recruiting presentation to their professional staff. Offer ride-along opportunities as well, so that they can see the job first hand. Many of these business professionals might be surprised to learn what police work is really like, and how much money police officers actually make.

Reach Out to Teachers and Education Students – This was another career area that almost always made the top five list, and was the highest ranked for female officers. Public school teachers must be educated, able to take charge of an unruly group of uncooperative individuals using only voice commands, and resolve conflicts on a daily basis. Almost all want to make a difference in society and are focused on helping people. Nevertheless, a 2017 nationwide study revealed that approximately 16% of public school teachers quit (not retire) every year, with only about half of them going on to another teaching job at a better school district. In other words, about 8% of public school teachers become disillusioned with their career choice every year.[3] If they meet your agency’s qualifications, a law enforcement career may allow these individuals to achieve the life purpose they sought in teaching, while giving them the authority to actually make a difference.

Just as with people within the business field, many working within education may not have an accurate image of the law enforcement career, or its salary. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics in 2016, the national average salary for a mid-career public school teacher in the U.S. (15+ years of experience and a master’s degree) was $56,000, with career-starting salaries still around $30,000 for those with a bachelor’s degree.[4] Make efforts to reach out to teachers, especially public school teachers with less than five years in the career, offering them materials about the profession and ride-along opportunities to see the law enforcement career first hand. Explain how their current job skills relate well to the skills needed in law enforcement. If you have a former teacher (or teachers) on your department, consider using them as the ones to reach out to these struggling, early-career teachers.

Reach Out to Nursing and Other Medical Students – Nurses have a turnover rate similar to that of teachers, however the vast majority of nurses and other medical professionals who quit their jobs simply go on to the same job with another employer. They are quitting their employers, not their careers.[5] Medical careers also generally offer equivalent or higher salaries than are offered by a law enforcement career.

However, the medical professions consistently made the top five list of alternative careers and the washout rate within nursing programs is extremely high. One study revealed that approximately 42% of nursing students in North Carolina do not successfully complete their nursing programs.[6] The academic factors most likely to wash out nursing students are courses in organic chemistry that require a good math aptitude, and physiology courses that require the memorization of all the hundreds of the body’s bones, organs, and their functions.[7] Despite weaknesses in these specific academic abilities, these failing students might still make excellent police officers—a career that offers exciting professional work and the ability to help people in times of crisis.

Law enforcement agencies should make efforts to reach out to local college nursing programs. Recruiters should sit down with the heads of these programs and offer to develop a partnership to talk to students whose academic performance in the nursing program has been less than satisfactory in the areas of math and science. Offer a recruiting presentation on campus that targets students in the medically-related programs that suggests law enforcement as an alternate career. Provide an accurate description of the law enforcement career field and encourage ride-along opportunities.

Consider Advertising Law Enforcement as a “Helping Profession” and a “Talking Profession” – Our data reveals that the strictly paramilitary aspects of law enforcement is not the draw that it once was. Particularly among those law enforcement officers hired within the last five years, careers in business and medicine significantly outrank the military as career alternatives to law enforcement.

Maintaining the pipeline of disciplined, mission-focused military veterans that transition into law enforcement seems vitally important. However, recruiters should be careful not to emphasize the similarities between law enforcement and the military at the expense of attracting qualified applicants who never seriously considered joining the military. Placing a disproportionate emphasis on engaging in pursuits and serving felony warrants might make it harder to attract the qualified individuals that law enforcement agencies need to attract—the applicants who are currently considering or engaged in careers in medicine, business, or education.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that there are career fields that can be mined for qualified individuals who might make excellent law enforcement officers—they just do not know it yet. Several professional career fields attract individuals who want the same things out of career that law enforcement can offer. What these individuals are lacking, perhaps, is accurate knowledge about the law enforcement career field and a personal invitation to apply. It is time we changed that.

References

[1] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2017). Business Employment Dynamics. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor.

[2] Workable Inc. (2019). Salary Profiles Report. San Francisco, CA: Workable Inc.

[3] Carver-Thomas, D. & Darling-Hammond, L. (2017). Teacher Turnover: Why It Matters and What We Can Do About It. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

[4] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2018). National Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor.

[5] Parveen, M., Maimani, K., & Kassim, N. M. (2017). Quality of work life: The determinants of job satisfaction and retention among RNs and OHPs. International Journal for Quality Research, 11(1), 173-194.

[6] Fraher, E., Belsky, D. W., Gaul, K., & Carpenter, J. (2010). Factors affecting attrition from associate degree nursing programs in North Carolina. Cahiers de sociologie et de démographie médicales, 50(2), 213-246.

[7] Smith, Linda; Engelke, Martha; Swanson, Melvin (2016). Student retention in associate degree nursing programs in North Carolina. Journal of Applied Research in the Community College, 23(1), 41-56.