Law enforcement agencies invest a great deal of time and money into each individual they hire as a law enforcement officer. As a result, having the ability to identify individuals who are likely to voluntarily resign their employment after a few years or even months would be extremely useful. If it were possible to identify such individuals before a hiring offer was made, it could help law enforcement agencies retain more officers and avoid wasting resources on people who are likely to leave around the time that they become effective officers. We examined this issue with the data from our DCG Police Recruiting and Hiring Survey to see if there were detectable differences between the officers most likely and least likely to stay with their current agency.

The Sample

Sworn law enforcement officers who attended the various training courses offered by the Dolan Consulting Group (DCG) from August 2018 through March 2019 were given the opportunity to participate in our DCG Police Recruiting and Hiring Survey. A total of 1,673 sworn personnel took the survey. Included in this survey were four questions that measured the respondents’ likelihood of staying with, or resigning from, their current law enforcement agency within the near future. These questions asked the respondents how strongly they agreed or disagreed with the following statements.

I am making an effort to find a new job with another employer within the next year.

I am actively looking for a job with other employers.

I plan to voluntarily quit my job soon.

I frequently think about ending my employment with this department.

Being of a sensitive nature, 15% of the respondents did not answer one or more of these questions. Another 29% of the respondents indicated that they had more than 20 years of career service, making them likely eligible for retirement if they chose to retire soon. We excluded these individuals to examine only those who both answered all the questions about quitting soon and had less than 20 years of service with their department.

We then examined the respondents’ likelihood of quitting soon by adding their scores from these four quitting statements, with responses of strongly disagree = 1 and strongly agree = 5. Approximately a third of the remaining participants had the lowest score possible (4 points), indicating they responded strongly disagree to all four of these statements about leaving. This group of 298 respondents was the third of the sample most likely to stay and least likely to leave before retirement. Approximately another third of the respondents (326 individuals) scored 10 or higher on this scale of likelihood of leaving, making them the group most likely to leave before reaching retirement. We eliminated the middle third of respondents and then compared just the responses of the two extremes—the third most likely to leave and the third most likely to stay— to see if they were drawn to their careers or employers for different reasons.

Reasons for Selecting this Career

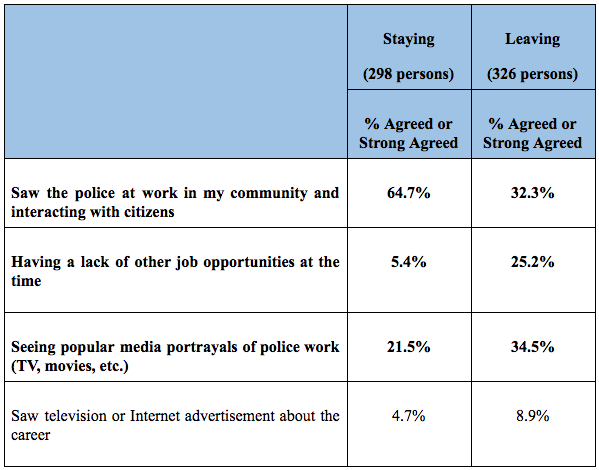

Both groups—those most likely to stay and those most likely to quit—were primarily drawn to the law enforcement career by a desire to help people, do interesting work, and through personal invitations to join the profession made by current law enforcement officers. Some notable differences, however, were revealed between these two groups. These four differences are displayed in Table 1 below.

The greatest difference between those most and least likely to quit their departments in the short term was the influence of having seen and interacted with the police working in their community. Two-thirds of those most likely to stay with their department had this experience while growing up, while only one third of those quitting had this experience.

Somewhat related to this is the fact that about 2 out of every 10 officers staying were drawn to the career by popular media portrayals of the police, while almost 4 out of every 10 officers quitting were drawn by popular media images. Those most likely to be quitting were also almost twice as likely to be swayed to pursue the career because of television or internet advertising.

These differences suggest that those staying had greater exposure and influence from seeing real law enforcement officers engaging in real police work, while those quitting were influenced more by the unrealistic portrayals of police work found within popular media. Obviously, those drawn to the career by seeing real examples of what the job entails would be less disillusioned than individuals drawn to the career by false media images of the career.

Table 1. Differences in Reasons for Selecting this Career

Another important difference between these two groups was the perceived lack of other career alternatives. Those most likely to quit were almost five times more likely to have said a lack of other job opportunities led them to pursue a law enforcement career. This strongly suggests that law enforcement was not their first career choice and not their life’s passion. A law enforcement career is very noble and rewarding, but it is also fraught with stress, frustration and danger. It should not be surprising that those who entered the law enforcement profession simply because they needed a steady job would be at much greater risk of quitting in the short term.

When screening applicants in oral review boards or written tests, agencies should consider examining these issues by asking the applicants pointed questions. What exposure does the applicant have to real police work? What does the applicant think a typical day of police work entails? What other career options does the applicant have? How long has the applicant wanted to be a law enforcement officer? Would the applicant still do the job if he or she had to take a pay cut? Law enforcement agencies should consider including a ride-along (or two or three) as part of the selection process so that the applicants can see the job firsthand. These findings also highlight the value of cadet, auxiliary, and reserve officer programs that allow potential future applicants to see the job firsthand and demonstrate their commitment to the profession by volunteering to participate without pay.

Reasons for Selecting their Specific Agency

Next, these two groups (quitting and staying) were compared to see if differences existed in why they chose to apply to, and accept employment with, their respective law enforcement agencies. Both those most and least likely to quit were drawn to their employing agencies by the pay, benefits package, and retirement plan. Beyond that, key differences were again revealed between these two groups with regard to what led them to their current employing agencies. These differences are displayed in Table 2 below.

Table 2. Differences in Reasons for Applying to this Particular Agency

Two important trends are revealed in Table 2. First, those most likely to stay were more likely to be drawn by the specific characteristics of their employing agency and community. Compared to those most likely to quit soon, those most likely to stay were more attracted to their department’s professional reputation and prestige, size, career opportunities, excitement level, and the safety level of where they could live. Please keep in mind that these respondents come from agencies and communities of all sizes. This means that those who are most likely to stay found the size, workload, and community of their agency to be a good fit for them. Those most likely to leave apparently did not place much importance on these fundamental aspects of the agency when applying to their departments and accepting the job offer.

The second important trend revealed by Table 2 is the fact that those most likely to quit perceived they had few other employment options and just took the first (or only) law enforcement job offer to come along. Compared to those most likely to stay, those most likely to quit soon were 33% more likely to agree with the statement, “I was attracted to my current employer because this was the first agency to offer me a job.” Also, those most likely to quit were four times more likely to agree with the statement, “I was attracted to my current employer because I lacked other job offers or opportunities at the time.” A law enforcement career is so demanding, and officers have so much authority and responsibility in the course of their duties, that we should not be hiring people as officers who are interested in the position as a last resort.

When screening applicants, law enforcement agencies should consider examining these two areas during their interviews as well. Ask applicants about the other employment prospects they might have – inside or outside of law enforcement. Ask applicants to specifically describe what attracted them to apply to your agency. Ask applicants what experiences they want out of their law enforcement career. Do they want to someday be a detective or a member of a specialized unit? There is nothing wrong with these career goals if your agency is large. If your agency is small, with few opportunities for specialty assignments, then this applicant has the potential to become a future disgruntled employee. It is important that you hire individuals who fit your agency’s size and culture. Furthermore, it is important that you avoid hiring people who have no better career options. There are probably very good reasons, linked to the applicant’s skills, attitudes, and behaviors, for why this applicant has few other career options.

Conclusion

In summary, it appears that there are some notable differences between those who are most or least likely to stay with your agency—differences that can be detected at the pre-employment stage. Those most likely to stay with your agency in the long term are more likely to have entered the career with a realistic view about the occupation—a view developed from seeing the job firsthand. Those most likely to quit the job in the short term are more likely to have entered the career with a false, entertainment media image of police work, thus becoming dissatisfied when the career was not what they had expected.

Those most likely to stay with your agency in the long term are more likely to have chosen a law enforcement career from several potential career options available to them. Those most likely to quit the job in the short term are more likely to have entered the career with fewer other employment options.

In short, people who stay chose a law enforcement career because they wanted to do so, and those who leave chose the career because they had few other options. Those most likely to stay with your agency in the long term are more likely to have selected employment with an agency that best fit their personality and career desires, while those most likely to quit gave less thought to the reputation, size, workload, or culture of their employing agency. Finally, those most likely to quit in the short term were more likely to just need a job—any job.

About the Authors

Dr. Richard Johnson serves as Chief Academic Officer for Dolan Consulting Group. In that capacity, he acts as the lead researcher in conducting DCG Recruiting and Retention Surveys throughout the United States.

Attorney Matt Dolan serves as Director for Dolan Consulting Group. He conducts training courses throughout the United States on the various topics, including Recruiting and Hiring for Law Enforcement.