The years following George Floyd’s in-custody death in 2020 have been bloody ones for the people of Minneapolis—particularly those living in low-income communities that were already experiencing the bulk of the city’s violent crime long before 2020.[1] The Minneapolis Police Department (MPD) has struggled to recover from a mass exodus of officers in the wake of Floyd’s death and the public outcry that followed. Staffing levels in 2025 are nearly 350 officers shy of where they were in 2020.[2] The public’s lack of trust in the MPD was exhibited by a public referendum in 2021 proposing to dismantle the department, which was narrowly rejected by only 56% of voters.[3] And a damning Department of Justice (DOJ) report released in June of 2023 was in no way disputed by the now second-term mayor Jacob Frey, who publicly stated that the report’s findings “are aligned with what communities of color have been telling us now for many years—in fact generations. Since May of 2020, we’ve been facing this reality on a daily basis.”[4]

Mayor Frey’s response in absolute agreement with the DOJ’s findings of organizational failure in 2023 is telling. Long before the in-custody death of George Floyd on May 25 of 2020, nearly 5 years ago, the signs of leadership failures in hiring, training, supervision, and discipline were evident—even from the outside looking in, let alone from the vantage point of the mayor’s office.

It would be tragic if law enforcement leaders across the country were not willing and able to learn from what happened 5 years ago in Minneapolis, how it happened, and why. Years of past leadership failures in the MPD were as apparent as they were avoidable. Other law enforcement agencies can and should learn from these mistakes.

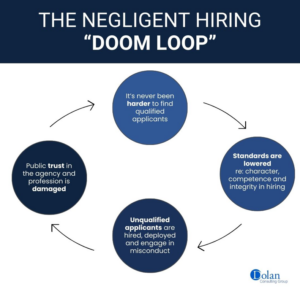

Applicants and new hires who showed early “red flags” in their backgrounds or poor on-the-job conduct were nonetheless allowed to pass their probationary periods and become permanent employees. Cops who engaged in blatant misconduct were sometimes fired but later reinstated due to internal affairs failures.[5] The process of choosing field training officers (FTOs) often put many of the same problem officers who engaged in misconduct in charge of training the MPD’s newest recruits. And policy violations continued year after year, without effective course correction or termination.

So, if police leaders and elected officials in Minneapolis were not focused on these fundamentals of police operations, what, exactly, were they focused on instead?

If Everything is a Priority, Then Nothing is a Priority

In the years leading up to George Floyd’s death, the MPD failed to demonstrate a commitment to training and practices in the fundamentals of police operations. Instead, the MPD leadership, and the elected leaders in the City of Minneapolis, focused on an assortment of policy and training priorities that seemed to capture the cultural moment and draw praise from outside groups—many of the same outside groups that would soon call for the dismantling of the MPD altogether. Many of these policy and training priorities had questionable utility for good policing and seem to have been pursued at the expense of the types of training and policies that every law enforcement agency needs.

The MPD was an early adopter of mandatory implicit bias training in 2014. MPD supervisors completed the training first, followed closely by patrol officers in 2015, and implicit bias training became a part of academy training and “refresher” trainings in 2015.[6] For many years, racial and gender diversity in recruiting and hiring was consistently touted as a top priority for MPD leadership, in an effort to make the ranks of the MPD reflect the racial and gender diversity of the city.[7]

In 2016, the MPD created a new transgender and gender non-conformity policy, requiring officers to address LGBTQIA+ individuals using their preferred pronouns.[8] This policy was touted by the MPD’s first female and first openly gay police chief, who had served as chief since 2012.[9] By 2019, the MPD created a six-member unit comprised of “civilian community navigator positions” including one dedicated to the LGBTQIA+ community.[10]

The MPD announced a broad rollout of body-worn cameras in 2016, and then-Chief Janee Harteau announced that “the officers are absolutely using their cameras.”[11] This rollout was accompanied by an agency-wide policy identifying the multitude of situations in which cameras were mandated to be activated, along with a warning that officers who failed to comply with the policy would “be subject to discipline, up to and including termination.”[12]

And in the months just prior to George Floyd’s death, the MPD mandated training in “dog de-escalation” techniques for all officers in the wake of incidents involving MPD officers shooting aggressive dogs.[13]

This article is not intended as a blanket condemnation of these training topics, policies, and initiatives. Each one deserves its own discussion for every law enforcement agency. But priorities matter, and the failure to prioritize sound hiring, training, supervision, and discipline by MPD leaders and elected city officials, while prioritizing nearly every new wave of training and policy alternatives, is possibly the organizational and leadership failure to be examined 5 years after the death of George Floyd.

Getting Back to Basics

It is dangerously easy to fall into the trap of chasing all the latest headline-grabbing training topics, while allowing the back-to-basics training to suffer, as the Minneapolis case painfully illustrates. This is particularly true when a very vocal few seem to drown out the many—with the latter group being much more concerned with commonsense quality-of-life issues than anything else.

In the early months of 2020, the MPD was publicly struggling to finally address a critical area of mismanagement which had been present for years—officer exhaustion in a management system where hours worked were simply not tracked. While publicly denying that there was any connection between officer fatigue and the poor decisions made by MPD officers in recent years, the city had recently settled for $20 Million in a deadly shooting case involving Officer Mohamed Noor, who had worked an off-duty shift for his secondary employer before reporting for work that day for the MPD.[14] When discussing the department’s failure to account for hours worked in relation to agency policies limiting off-duty hours, Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey concluded, “If we can’t track hours worked, that’s not good.”[15]

This $20 Million settlement stemmed from the deadly MPD shooting of Justine Damond on July 15, 2017.[16] Damond called 911 to report what she believed to be a sexual assault in progress nearby. A two-man squad car responded to her call and approached her residence from the rear alley. Damond, the complainant witness, a middle-aged woman dressed in pajamas, approached the driver’s side door to speak with the officers when she was inexplicably shot and killed by the officer in the passenger seat—Officer Mohammed Noor.[17] The deadly shooting of the unarmed complainant resulted in a $20 million civil settlement and a five-year prison term for Noor.[18] A relatively recent hire by the MPD, Noor’s field training officers had documented critical performance issues exhibited by Noor, but somehow that did not prevent him from completing his probationary term and becoming a full-fledged member of the MPD.[19] Then-Mayor Betsy Hodges publicly praised the newly hired Noor in 2016, stating that:

Officer Noor has been assigned to the 5th Precinct, where his arrival has been highly celebrated, particularly by the Somali community in and around Karmel Mall.[20]

In the years preceding George Floyd’s death, the leadership in the MPD demonstrated basic deficiencies in internal affairs operations, first-line supervision, and other fundamentals of personnel management in a law enforcement agency. Instead of focusing on correcting these deficiencies, in the immediate aftermath of George Floyd’s death, leadership in the MPD and the City of Minneapolis publicly blamed arbitrators, who, they claimed, prevented bad cops from being fired without later being reinstated.[21]

By the end of 2020, the MPD’s own failures in conducting internal affairs investigations were becoming clear to anyone examining the cases of arbitrators overturning MPD’s disciplinary decisions. These internal affairs failures were so significant that, on December 29 of 2020, Mayor Frey and then-Chief Medaria Arradondo, who had previously led the Internal Affairs Unit, announced major changes. Frey publicly acknowledged that the MPD’s accountability failures were of their own making. He announced that their Internal Affairs Unit investigators would begin working closely with city attorneys to ensure that internal investigations were conducted thoroughly and lawfully in order to minimize the risk of legitimate discipline being overturned at arbitration. This decision came following years of internal failures to impose discipline in a fair, consistent, and timely manner, which led to many cases of police misconduct going unpunished.[22]

Frey publicly lamented the state of internal affairs operations and the resulting reinstatements of officers who had engaged in misconduct, but who were ultimately reinstated due to MPD failures in conducting fair, timely, and lawful administrative investigations. Frey stated at the time, “We, as a city, cannot allow a file languishing on an overworked investigator’s desk to boost the odds of a bad cop being put back on the street.”[23]

To summarize, in the years leading up to the death of George Floyd, MPD priorities included implicit bias training, policies on the use of gender pronouns in the field, diversifying the ranks, and dog de-escalation tactics. MPD priorities did not include effectively addressing officer fatigue, properly vetting new hires in field training for their ability to safely do the job, or competently conducting internal affairs investigations into allegations of serious police misconduct.

It’s Not What You Preach, It’s What You Tolerate

In March of 2020, if one had judged a police department by the sweeping statements made at press conferences, one would have been tempted to view the MPD as one of the most progressive, forward-thinking departments in the country. But, in between press conferences, accountability was undoubtedly lacking.

As mentioned previously, the MPD announced a broad rollout of body-worn cameras in 2016, at which time then-Chief Janee Harteau announced that “the officers are absolutely using their cameras.”[24] But when Justine Damond was inexplicably shot and killed by MPD Officer Noor in 2017, neither he nor his partner had activated their body-worn cameras. When other officers arrived on the scene and found out what had happened, they selectively turned their cameras off at various times during the investigation.[25] In 2019, it was announced that officers’ compliance with the body-worn camera policy was improving, although 70 officers still required mandatory training to address non-compliance. Mayor Frey indicated that, moving forward, discipline could result from non-compliance. Approximately 3 years after the public proclamation by the MPD police chief that the cameras were on and rolling, the Minneapolis mayor had to publicly acknowledge that, far too often, the body-worn cameras were not being used as had been promised.

In spite of the implicit bias training sessions and public proclamations on diversity, the death of George Floyd must ultimately be viewed as a failure of fundamental police ethics. For all the focus within the MPD leadership on racial disparities, racial discrimination, and racial bias, it must be noted that George Floyd was not determined to be the victim of a hate crime. Minnesota’s Attorney General, who was intimately involved in the criminal prosecution of Derek Chauvin, indicated in an interview with 60 Minutes in 2021, that Officer Chauvin was not charged with a hate crime due to lack of evidence.[26]

When asked by the interviewer if the in-custody death of George Floyd was a hate crime, Attorney General Ellison responded:

We don’t have evidence that Derek Chauvin factored in George Floyd’s race as he did what he did….In order for us to stop and pay serious attention to this case and be outraged by it, it’s not necessary that Derek Chauvin had a specific racial intent to harm George Floyd.[27]

This fact, possibly more than any other, should inform the way that police leaders look at training and policy priorities in 2025. It is a fact that points to the importance of back-to-basics policy development and training that focuses on words, actions, and outcomes rather than unknowable, invisible biases and other concerns that are often the subject of agency policies and training.

From vetting new hires to holding veteran officers accountable, from training priorities to internal affairs operations—the consistent failures of MPD and elected officials in the years prior to George Floyd’s death show an agency that was far more dysfunctional than most law enforcement agencies in the United States. And that dysfunction appears to have ultimately been rooted in a lack of commonsense priorities.

About the Author

Matt Dolan, J.D.

Matt Dolan is a licensed attorney who specializes in training and advising public safety agencies in matters of legal liability, risk management and ethical leadership. His training focuses on helping agency leaders create ethically and legally sound policies and procedures as a proactive means of minimizing liability and maximizing agency effectiveness.

A member of a law enforcement family dating back three generations, he serves as both Director and Public Safety Instructor with Dolan Consulting Group.

In December of 2024, he published his first book, Police Liability: A Guide for Law Enforcement Leaders of All Ranks.

His training courses include Internal Affairs Investigations: Legal Liability and Best Practices, Supervisor Liability for Law Enforcement, Recruiting and Hiring for Law Enforcement, Confronting the Toxic Officer, Performance Evaluations for Public Safety and Confronting Bias in Law Enforcement.

Disclaimer: This article is not intended to constitute legal advice on a specific case. The information herein is presented for informational purposes only. Individual legal cases should be referred to proper legal counsel.

References

[1] Lou Raguse, “Minneapolis Had More Homicides in 2024 than 2023”, KARE 11 News, January 1, 2025. Accessed March 5, 2025 at: https://www.kare11.com/article/news/local/minneapolis-had-more-homicides-in-2024-than-2023/89-c047909f-aa1a-4a81-ace7-97a13f6cff83#:~:text=In%20Minneapolis%2C%20there%20were%2048,to%20Minneapolis%20Police%20crime%20data.

[2] Jason Rantala, “Minneapolis Police Boost Numbers for the First Time in 5 Years,” CBS WCCO News, January 12, 2025. Accessed March 5 at: https://www.cbsnews.com/minnesota/news/minneapolis-police-boost-numbers-5-years/

[3] Martin Kaste, “Minneapolis Voters Reject a Measure to Replace the City’s Police Department,” NPR News, November 3, 2021. Accessed March 5, 2025 at: https://www.npr.org/2021/11/02/1051617581/minneapolis-police-vote

[4] KMSP Fox 9 News, “Minneapolis Police Investigation: DOJ Found It Violated People’s Constitutional Rights,” KMSP Fox 9 News, June 16, 2023. Accessed March 6 at: https://www.fox9.com/news/minneapolis-police-department-doj-investigation-results

[5] Brandt Williams, “Minneapolis Officer Ordered Back on the Job after Firing for Punching Handcuffed Man,” Minnesota Public Radio News, December 2, 2019. Accessed on March 6, 2025 at: https://www.mprnews.org/story/2019/12/02/minneapolis-officer-ordered-back-on-the-job-after-firing-for-punching-handcuffed-man

[6] Nicole Norfleet, “Minneapolis Police Training Aims to Help Officers Recognize Biases,” Minnesota Star Tribune, June 24, 2015. Accessed on March 8, 2025 at: https://www.startribune.com/minneapolis-police-training-aims-to-help-officers-recognize-biases/309674441

[7] KMSP FOX 9 News, “Graduating Minneapolis Police Officers Reflect on Diversity,” KMSP FOX 9 News, November 1, 2017. Accessed on March 6, 2025 at: https://www.fox9.com/news/graduating-minneapolis-police-officers-reflect-on-diversity; Libor Jany, “With Few Women in Top Spots, Minneapolis Police Face a Challenge Diversifying Force: Chief “Committed to Doing More” to Diversify Ranks,” Minnesota Star Tribune, April 1, 2018. Accessed on March 6, 2025 at: https://www.startribune.com/with-few-women-in-top-spots-minneapolis-police-face-a-challenge-diversifying-force/478499673; Brandt Williams, “Minneapolis Police Make An Effort To Hire More Minority Officers,” National Public Radio Morning Edition, September 3, 2014. Accessed on March 6, 2025 at: https://www.npr.org/2014/09/03/345308385/minneapolis-pd-makes-an-effort-to-hire-more-minority-officers

[8] Libor Jany, “Minneapolis Police Announce New Transgender, Gender Nonconformity Policy: The New Rules Will Require Officers to Address Transgender People Using Their Preferred Names and Pronouns,” Minnesota Star Tribune, September 22, 2016. Accessed on March 6, 2025 at: https://www.startribune.com/mpls-police-announce-new-transgender-gender-nonconformity-policy/394319441

[9] Brandt Williams, “Janee Harteau Sworn In as Minneapolis Police Chief,” Minnesota Public Radio News, December 4, 2012. Accessed on March 6, 2025 at: https://www.mprnews.org/story/2012/12/04/janee-harteau-sworn-in-as-mpls-police-chief

[10] Libor Jany, “New Minneapolis Police Liaison Works to Build Bridges to LGBTQ Community,” Minnesota Star Tribune, June 21, 2019. Accessed on March 6, 2025 at: https://www.startribune.com/new-minneapolis-police-liaison-works-to-build-bridges-to-lgbtq-community/511659802

[11] Barndt Williams, “Minneapolis Police Say Body Cameras Showing Immediate Benefits,” Minnesota Public Radio News, November 2, 2016. Accessed on March 6, 2025 at: https://www.mprnews.org/story/2016/11/02/minneapolis-police-say-body-cameras-showing-immediate-benefits

[12] Barndt Williams, “Minneapolis Police Say Body Cameras Showing Immediate Benefits,” Minnesota Public Radio News, November 2, 2016. Accessed on March 6, 2025 at: https://www.mprnews.org/story/2016/11/02/minneapolis-police-say-body-cameras-showing-immediate-benefits

[13] CBS WCCO News, “Minneapolis Police Officers Take Training to Better Handle Aggressive Dogs,” CBS WCCO News, January 22, 2020. Accessed February 16, 2024 at: https://www.cbsnews.com/minnesota/news/minneapolis-police-required-to-take-dog-sensitivity-training/.

[14] Matt Sepic, “Task Force to Look at Minneapolis Cops’ Off-Duty Work,” Minnesota Public Radio News, February 6, 2020. Accessed April 7, 2024 at: https://www.mprnews.org/story/2020/02/06/task-force-to-look-at-minneapolis-cops-offduty-work.

[15] Leah Beno, “Minneapolis Task Force to Reexamine MPD Off-Duty Employment Policies,” KMSP Fox 9 News, February 5, 2020. Accessed April 8, 2024 at: https://www.fox9.com/news/minneapolis-task-force-to-reexamine-mpd-off-duty-employment-policies.

[16] Amy Forliti, “Minneapolis to Pay $20 Million to Family of 911 Caller Slain by Cop,” Associated Press, May 3, 2019. Accessed on March 8, 2025 at: https://apnews.com/article/6362cd8e99c74816863622f7daf9ebf1

[17] MPR News, “Video: Confusion, Disbelief as MPD Officers Rush to Ruszczyk Shooting,” MPR News, May 24, 2019. Accessed on March 8 at:

[18] Associated Press, “Ex-Minneapolis Police Officer Mohamed Noor Released from Prison in Fatal Shooting of Justine Ruszczyk Damond,” Associated Press, June 27, 2022. Accessed on March 8, 2025 at: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/amp/rcna35527

[19] KMSP Fox 9 News, “Prosecutors: Mohamed Noor’s Work History Shows ‘Reckless Disregard for Human Life,’” KMSP Fox 9 News, September 6, 2018. Accessed on March 8, 2025 at: https://www.fox9.com/news/prosecutors-mohamed-noors-work-history-shows-reckless-disregard-for-human-life.amp

[20] David Chanen and Faiza Mahamud, “What We Know About Mohamed Noor, Minneapolis Officer who Fatally Shot Justine Damond,” Minnesota Star Tribune, July 18, 2017. Accessed on March 8, 2025 at: https://www.startribune.com/what-we-know-about-mohamed-noor-minneapolis-officer-who-fatally-shot-justine-damond/435018163

[21] KMSP Fox 9 News Staff, “Minnesota Mayors Call On State Lawmakers to Overhaul Police Arbitration Process,’” KMSP Fox 9 News, June 18, 2020. Accessed on March 8, 2025 at: https://www.fox9.com/news/minnesota-mayors-call-on-state-lawmakers-to-overhaul-police-arbitration-process.amp

[22] Jeremiah Jaconsen, “Minneapolis Police Disciplinary Changes.” Minneapolis KARE 11 News, December 29, 2020. Accessed February 20, 2024 at: https://www.kare11.com/article/news/local/minneapolis-policeannounce-disciplinary-process-changes/89-7eb47ff3-8125-4c3c-839f-dc0df7bced92.

[23] MPR News Staff, “Minneapolis Announces Changes to Police Misconduct Investigations,” MPR News, December 29, 2020. Accessed on March 8, 2025 at: https://www.mprnews.org/story/2020/12/29/minneapolis-announces-changes-to-police-misconduct-investigations

[24] Barndt Williams, “Minneapolis Police Say Body Cameras Showing Immediate Benefits,” Minnesota Public Radio News, November 2, 2016. Accessed on March 6, 2025 at: https://www.mprnews.org/story/2016/11/02/minneapolis-police-say-body-cameras-showing-immediate-benefits

[25] Probable Cause and Information Charging Document, State of Minnesota vs. Mohamed Mohamed Noor. State of Minnesota, County of Hennepin, March 20, 2018. Accessed on March 6, 2025 at: https://web.archive.org/web/20180925104317/https://www.hennepinattorney.org/-/media/Attorney/NEWS/2018/Noor-Mohamed-cplt.pdf

[26] Scott Pelley, “60 Minutes Interviews the Prosecutors of Derek Chauvin,” CBS News, April 26, 2021. Accessed on March 8, 2025 at: https://www.cbsnews.com/amp/news/derek-chauvin-prosecutors-george-floyd-death-60-minutes-2021-04-25/

[27] Ibid.