In your community, is elementary, middle, and high school enrollment down? With the exception of a few private schools that have seen a recent influx of students, are schools closing and consolidating? Do you notice more retirement age citizens than in past years, and fewer young people? Is your community building 55 and over living communities and senior citizen facilities more rapidly than traditional family homes and childcare centers? Is your community building as many dog parks for pets as playgrounds for children? If not, your community is the exception to the rule across the United States.

The latest U.S. Census data showed that the share of the U.S. population that is 65 years old or over has increased by more than 33% in just 10 years.[i] Even in localities that are seeing an influx of newcomers, like Fort Worth, Texas, more residents does not necessarily mean more school age children.[ii] The same is true in Phoenix.[iii] The same is true in South Florida.[iv] The list goes on.

As for the localities that have not seen growing populations driven by newly arriving residents, the picture is even more striking. In states like Illinois, Ohio, and New York, that have not seen an influx in new residents, the school closures seem even more pronounced and this extends to cutbacks at many colleges and universities.

At the same time, aging populations are causing alarm in light of the burdens that these demographic shifts will result in for those depending on accessible health care and pensions, as well as those expected to provide those services and pay into those systems.[i]

The rapid aging of the U.S. population, which is set to accelerate in the coming years, will have profound impacts on our society across a multitude of different areas. Law enforcement is likely no exception.

What an Aging Population Means for Police Recruiting and Staffing

In discussing the challenges of recruiting and retention with law enforcement leaders across the country, a constant theme emerges—an apparent lack of qualified applicants in the generation of young men and women entering young adulthood. This is not unlike the challenge facing countless other public service professions and the military.

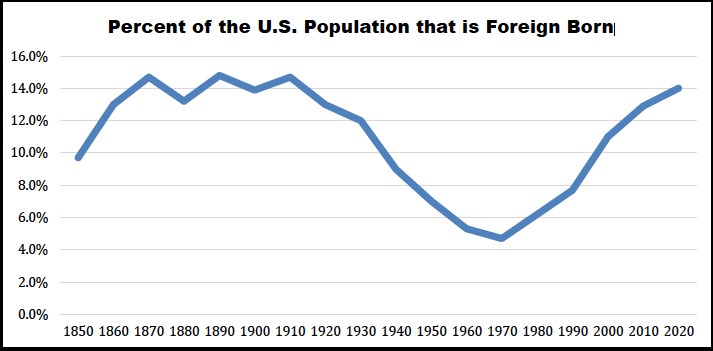

One of the key components of the challenge is the lower birth rate over recent decades, which is resulting in fewer numbers of available applicants—even before considering issues of mental health, drug addiction, obesity, and other issues that make Generation Z (those born in 1997 or after) a particularly challenging applicant pool.

At the same time, thousands of officers who joined the profession 20 or 30 years ago are becoming eligible for retirement and are doing so. Recently, the executive leadership of the Cincinnati Police Department illustrated this reality in noting that, even if recruiting efforts in the coming years were successful, the retirement cliff facing the agency could not be avoided.[ii]

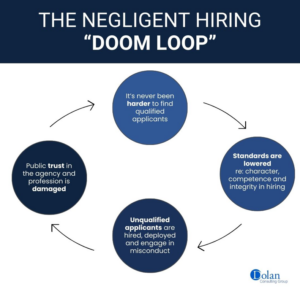

All available demographic indicators point to the reality that the ranks of law enforcement will be thinning, barring an unethical and counter-productive lowering of standards—as has occurred in some agencies and which the Department of Justice has advocated for in a recent report.[iii] But if agencies maintain ethically and legally defensible hiring standards, their numbers of sworn officers are very likely to become smaller in many jurisdictions.

So, does this mean that alarm bells should be ringing and that we should anticipate decades of unchecked criminal activity as so many officers retire and so few are sworn in? Not necessarily. There is another side of this population equation that is found in the shrinking numbers of young adults—the population segment statistically more likely to engage in violent crime.

In a sense, the same recruiting and staffing challenges facing law enforcement agencies may face the gangs who recruit young people to prey on the community.

What an Aging Population Means for Rates of Violent Crime

There seem to be two sides of the coin when it comes to the aging U.S. population as it relates to law enforcement. On one side, as we have discussed, is the likelihood of less officers—at least in many jurisdictions. On the other side, is the likelihood of fewer young people and, therefore, a smaller population of those most likely to commit violent crimes.

Across cultures and over generations, we see that the prime demographic of violent law breakers tends to be young adult and male. When sheriffs and police chiefs discuss combating violent crime, are they referring to their community’s elderly population as the perpetrators? How many task force mass arrests of violent offenders involve the mug shots of offenders in their 60s and above? For those serving long prison terms, what percentage of them committed their crimes in middle or old age?

The answers to these questions are obvious. Older people are statistically unlikely to become perpetrators of violent crime. So, as the young adult population shrinks, it would make sense to expect less violent crime. Could these demographic realities help to explain the drop in homicides and other violent crimes that we are seeing in some cities across the country—particularly in spite of the fact that so many agencies are engaging in less proactive policing than in recent years—either due to staffing shortages, political interference, or officer morale?[iv]

In June of 2023 in Michigan, local news reports indicated that the number of sworn law enforcement officers in the state has gone down 19% since 2001—decreasing from 23,000 to 18,500. This decrease led to one Michigan police chief describing his staffing challenges and asking, with reference to the labor shortage facing law enforcement and other employers in the area, “Where did everyone go?”[v]

In October of 2023, just a few months later, the State of Michigan announced that it was devoting significant resources to an advertising campaign aimed at convincing young people and families to move to Michigan.[vi] Michigan’s efforts to turn the tide on the aging population were also put into stark terms in January of this year at the annual Detroit Policy Conference. Among those policy experts voicing concerns was former U.S. Ambassador John Rakolta Jr. Ambassador Rakolta told the audience: “The further behind we get, it will be almost impossible, at some point to catch up… By 2050, we’ll be lucky to be the same size state as we are today, and there’s just enormous implications as a result of that.”[vii]

This reality of declining law enforcement ranks coinciding with broader concerns over a shrinking working age population is not unique to Michigan, although that state may face more demographic decline than most. Michigan’s predicament is not an isolated one, and law enforcement leaders across the country should work to understand their jurisdiction’s changing age demographics in order to understand the operational realities that lie ahead.

Paradigm Shifts for Law Enforcement Leaders as the Population Gets Older

As law enforcement leaders seek to determine what their authorized strength should be with respect to sworn officers, simply looking to population numbers may be insufficient. How many officers should an agency have as its authorized strength? Should it be based on officers per 100,000 population? Or should agencies look for a new and more precise measure that takes into account the percentage of the population which is between the ages of, for instance, 15 and 30?

In closing, it is important to note that this article does not propose that the need for proactive policing practices will no longer be a vital part of public safety. There are and will continue to be hot spots of crime—dots on which to place cops. Violent crime is and will sadly continue to be an ever-present danger, particularly in communities suffering from poverty and social breakdown.

The issue is one of scale. Can a motivated, proactive police force of 300 officers do the work that was required of 400 officers generations ago due to the demographic realities? Is it possible that many agencies will be tasked with doing less with less in terms of personnel resources in the years ahead as the number of violent offenders declines as a result of demographic trends?

These questions and more should be a part of the conversations that law enforcement leaders have in the years ahead involving staffing and operations in light of an aging population—a rarely discussed topic that will likely have a dramatic effect on fighting crime.

About the Author

Matt Dolan, J.D.

Matt Dolan is a licensed attorney who specializes in training and advising public safety agencies in matters of legal liability, risk management and ethical leadership. His training focuses on helping agency leaders create ethically and legally sound policies and procedures as a proactive means of minimizing liability and maximizing agency effectiveness.

A member of a law enforcement family dating back three generations, he serves as both Director and an instructor with Dolan Consulting Group. He has trained thousands of law enforcement professionals over the last decade.

His training courses include What Does an Aging Population Mean for Law Enforcement?, Internal Affairs Investigations: Legal Liability and Best Practices, Supervisor Liability for Law Enforcement, Recruiting and Hiring for Law Enforcement, Confronting the Toxic Officer, Performance Evaluations for Public Safety and Confronting Bias in Law Enforcement.

Disclaimer: This article is not intended to constitute legal advice on a specific case. The information herein is presented for informational purposes only. Individual legal cases should be referred to proper legal counsel.

References

[1] U.S. Census Bureau, Press Release Number CB23-106, America Is Getting Older: New Population Estimates Highlight Increase in National Median Age (Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau, June 22, 2023). Accessed on 03/08/2024 at: https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2023/population-estimates-characteristics.html; Mike Schneider, “With Population of Aging Americans Growing, U.S. Median Age Jumps to Nearly 39,” NPR News, May 25, 2023. Accessed on 03/08/2024 at: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/amp/nation/with-growing-population-of-aging-americans-u-s-median-age-jumps-to-nearly-39

[2] Silas Allen, “Fort Worth ISD Could Shut Some Campuses Down Due to Enrollment Declines: They Aren’t Alone,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, February 20, 2024. Accessed on 03/08/2024 at: https://amp.star-telegram.com/news/local/education/article285571942.html

[3] Micaela Marshall, “Paradise Valley Unified Considers Closing 4 Schools Amid Declining Enrollment,” CBS Channel 5 News, December 7, 2023. Accessed on 03/08/2024 at: https://www.azfamily.com/2023/12/07/paradise-valley-unified-considers-closing-4-schools-amid-declining-enrollment/

[4] Ana Claudia Chacin and Jimena Tavel, “Which Broward Schools May Be at Risk of Closing? Enrollment Numbers May Provide Answers,” Miami Herald, February 2, 2024. Accessed on 03/08/2024 at: https://www.miamiherald.com/news/local/education/article285935171.html

[5] William Brangham and Layla Quran, “How an Aging Population Poses Challenges for U.S. Economy, Workforce and Social Programs,” PBS News, June 27, 2023. Accessed on 03/08/2024 at: https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/how-an-aging-population-poses-challenges-for-u-s-economy-workforce-and-social-programs

[6] Cameron Knight, “Without Action, Police Staffing Could Plummet by 2029,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 21, 2023. Accessed on 03/08/2024 at: https://www.cincinnati.com/story/news/local/2023/03/21/cincinnati-police-department-faces-2029-cliff-for-staffing/70033027007/

[7] Bureau of Justice Assistance and Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, Recruitment and Retention for the Modern Law Enforcement Agency: Revised (Washington, DC: Office of Community Oriented Policing Services, 2023) 3-4.

[8] Bill Hutchinson, “It is Historic: US Poised to See Record Drop in Yearly Homicides Despite Public Concern Over Crime: The Year is Expected to End with Over 2,000 Fewer Murders Than in 2022,” ABC News, December 28, 2023. Accessed on 03/08/2024 at: https://abcnews.go.com/US/homicide-numbers-poised-hit-record-decline-nationwide-americans/story?id=105556400

[9] EUP News Staff, “Michigan’s Police Officer Shortage Becoming Dire: Where did everyone go?” EUP News, July 26, 2023. Accessed on 03/08/2024 at: https://www.eupnews.com/2023/07/michigans-police-officer-shortage-becoming-dire-where-did-everyone-go/

[10] State of Michigan, Office of the Governor, Press Release: Gov. Whitmer Launches ‘You Can in Michigan’ National Marketing Campaign to Grow Economy, Attract and Retain Talent (Lansing, MI: State of Michigan, Office of the Governor, October 10, 2023). Accessed on 03/08/2024 at: https://www.michigan.gov/whitmer/news/press-releases/2023/10/10/whitmer-launches-you-can-in-michigan-national-marketing-campaign-to-grow-economy

[11] Andres Gutierrez, “Detroit Leaders Finding Solutions to Declining Population,” CBS News Detroit, January 11, 2024, Accessed on 03/08/2024 at: https://www.cbsnews.com/detroit/news/detroit-leaders-finding-solutions-to-declining-population/?_cldee=jMLtSixTBTkDbWIvIIZog4q1WsnTxHCvyPIgjIGkrW1PlblS-YrYi_XQrvqHz4Yg&recipientid=contact-d8c3f41970b5e51180ea3863bb35cf60-2e3b20862ab342d0b67414f244d335f5&esid=7de4d130-acb0-ee11-a569-6045bd006576